I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused.

I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused.

Her perception of judicial bias against criminal plaintiffs is one shared by many and not without cause.

By contrast, I’ve heard from hundreds of people (of both genders) who’ve been violated by false accusers in civil court and who know that frauds are readily and indifferently accepted by judges. (Correspondingly, more than one female victim of civil restraining order abuse has characterized her treatment in court and by the courts as “rape.”)

Their perception of judicial bias against civil defendants is equally validated.

Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male.

Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male.

The failures of the court in the prosecution of crimes against women, which arouse feminist ire like nothing else, are largely responsible for the potency of restraining order laws, which are the product of dogged feminist politicking, and which are easily abused to do malice (or psychological “rape”).

In ruminating on sexual politics and the justice system, I’m inexorably reminded of the title of a book by psychologist R. D. Laing that I read years ago: Knots.

In the first title I conceived for this piece, I used the phrase “can’t see eye to eye.” The fact is these issues are so incendiary and prejudicial that no one can see clearly period. Everyone just sees red.

Under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), federal funds are doled out to police precincts and courts in the form of grants purportedly intended to educate police officers and judges and sensitize them to violations against women, which may have the positive effect of ensuring that more female victims of violent crimes see justice but simultaneously ensures that standards applied to the issuance of civil restraining orders slacken still further, allowing casual abuse of a free process to run rampant and destroy lives. The victim toll of false restraining orders negates strides made toward achieving justice for female victims in criminal prosecutions. What is more, though restraining orders are four times more often applied for by women than men, making women their predominant abusers, the laxity of restraining order administration allows women to be violated by men, too.

Not only was a woman I’ve recently been in correspondence with repeatedly assaulted by her short-term boyfriend, a charming and very cunning guy; he also succeeded in petitioning a false restraining order against her, alleging, among other things, violence. She had even applied for a restraining order against him first, which was dismissed:

There are no words for how I felt as I walked to my car that afternoon. To experience someone I had cared deeply about lying viciously in open court, to have a lawyer infer that I’m a liar, and to be told by a judge that, basically, he didn’t believe me (i.e., again, that I’m a liar), filled me with a despair so intense that I could hardly live with it. You know how, in trauma medicine, doctors will sometimes put grossly brain-injured patients into medically-induced comas so as to facilitate healing? That afternoon, I needed and longed for a medically-induced emotional coma to keep my skull from popping off the top of my head. I don’t know how else to describe it. It was that day that I learned that the justice system is rotten, that the truth doesn’t mean shit, and that to the most depraved liar go the spoils.

As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

The perception that consequences of civil frauds are no big deal is wrong and makes possible the kind of scenario illustrated by this woman’s case: the agony and injury of physical assault being exacerbated by the agony and injury of public shame and humiliation, a psychological assault abetted and intensified by the justice system itself.

The consequences of the haywire circumstance under discussion are that victims multiply, and bureaucrats and those who feed at the bureaucratic trough (or on what spills over the side) thrive. The more victims there are and the more people there are who can be represented as victims, the busier and more prosperous grow courts, the police, attorneys, advocacy groups, therapists, etc.

What’s glaringly absent in all of this is oversight and accountability. Expecting diligence and rigor from any government apparatus is a pipedream. So is expecting people to be honest when they have everything to gain from lying and nothing to lose from getting caught at it, because false allegations to civil courts are never prosecuted.

Expecting that judges will be diligent, rigorous, and fair if failing to do so hazards their job security, and expecting civil plaintiffs to be honest if being caught in a lie means doing a stint in prison for felony perjury—that, at least, is reasonable.

The obstacle is that those who hold political sway object to this change. The feminist establishment, whose concern for women’s welfare is far more dogmatic than conscientious, has a strong handhold and no intention of loosening its grip.

Typically both criminal allegations of assault or rape and civil allegations in restraining order cases (which may be of the same or a similar nature) boil down to he-said-she-said. In criminal cases, the standard of guilt is proof beyond a reasonable doubt, a criterion that may be impossible to establish when one person is saying one thing and the other person another, evidence is uncertain, and there are no witnesses. In civil cases, no proof is necessary. So though feminist outrage is never going to be fully satisfied, for example, with the criminal prosecution of rapists, because some rapists will always get off, feminists can always boast success in the restraining order arena, because the issuance of restraining orders is based on judicial discretion and requires no proof at all; and the courts have been socially, politically, and monetarily influenced to favor female plaintiffs. However thwarted female and feminist interests may be on the criminal front, feminists own the civil front.

And baby hasn’t come a long way only to start checking her rearview mirror for smears on the tarmac now.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states.

Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states. You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

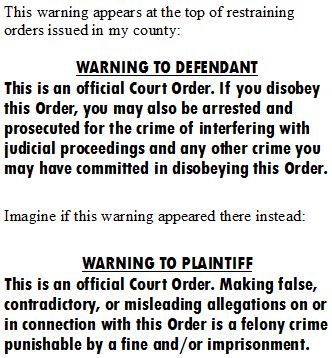

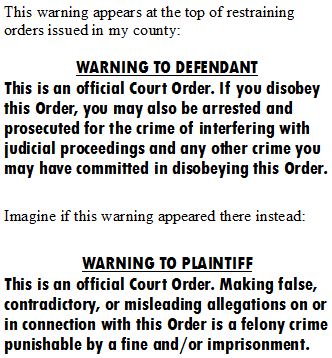

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.