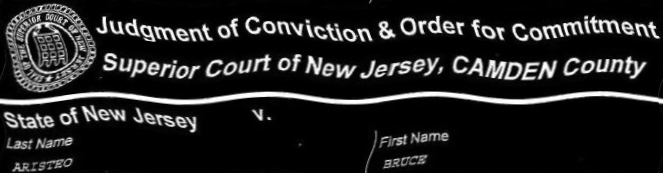

Matthew S. Chan is the creator and administrator of ExtortionLetterInfo.com (ELI) and the appellant in the Georgia Supreme Court case Chan v. Ellis.

In my desire to give something back to RestrainingOrderAbuse.com (ROA) for the enormous help, contribution, and insights into my own protective order appeal case with the Georgia Supreme Court that it provided, I found myself a bit stumped as to what to write about that might be helpful and perhaps a bit different from the articles and commentaries I have read on ROA so far. So, if I make some wrong assumptions about ROA, please forgive me as I am a relative newcomer. As a disclaimer, I do not feel qualified to speak specifically on matters of domestic protective/restraining orders as they relate to divorces, custody fights, or other family disputes. I feel those issues are highly volatile, and I don’t have the background to properly discuss them.

What I do feel qualified to speak on, however, are matters that pertain to the First Amendment, free speech, and that speech as it relates to online speech. Whether disputing parties are related or not, the First Amendment, backed by many significant rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court, makes it clear that everyone in the U.S. (including murderers, rapists, robbers, embezzlers, and any other type of criminal you can name) enjoys the right to free speech. That free speech comes with certain exceptions and restrictions as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Some of them are:

- Incitement

- Defamation (including libel and slander)

- Obscenities, such as child pornography

- Fighting words

It is almost always legal to engage in speech about someone publicly or privately, unflattering or not. But it is not always acceptable to engage in speech to a person, especially if it is unwanted. In the context of the Internet, you should have the right to speak freely about anything or anyone as long as your speech doesn’t fall within the list of exceptions and restrictions.

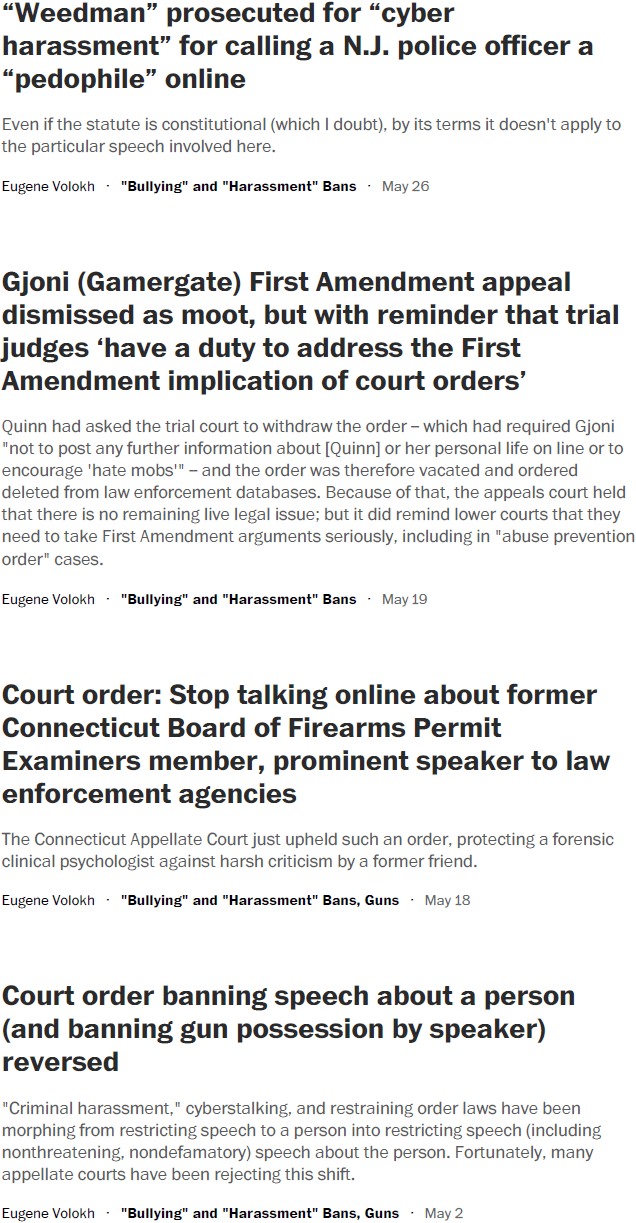

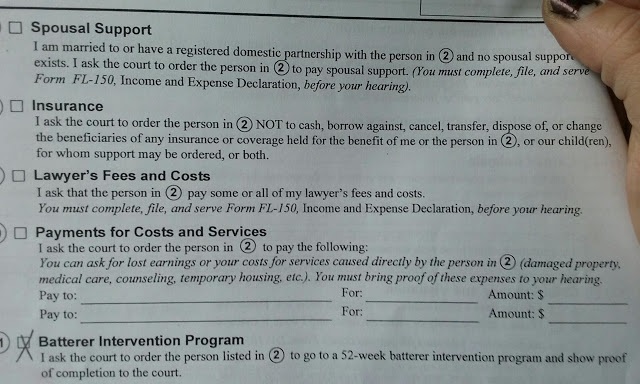

And yet, I am hearing more about these underground restraining orders that instruct people to be absolutely silent regarding a certain person or party, i.e., that dictate you cannot speak publicly about that person or party to anyone. That is clearly unconstitutional.

This is an abuse of the protective/restraining order system that frequently happens in courts of local and smaller jurisdictions. It is no surprise that many of these cases involve “pro se” (self-represented) parties, who are more likely to be taken advantage of by an overzealous and overstepping judge. Up to this point, I have stated what most ROA readers already know.

But what then can you do about it? The easy, copout answer is hire a good lawyer. But we all know “pro se” parties represent themselves because they either can’t find a good lawyer or they can’t afford a good lawyer.

But what then can you do about it? The easy, copout answer is hire a good lawyer. But we all know “pro se” parties represent themselves because they either can’t find a good lawyer or they can’t afford a good lawyer.

Having lived with a protective order for nearly two years, I have found that it largely doesn’t impact my day-to-day existence. I have very little emotional baggage about it. Although my protective order is a matter of public record, it is not easily found, nor is it advertised. However, my accuser chooses to make mine public as a way to get revenge/payback and to embarrass and humiliate me. I don’t feel embarrassed or humiliated at all anymore. I’ve had two years to let it sink in. She went to her local newspaper as well as a photography blog site to publicize my protective order. I am very certain she approached several other media sources, but she only managed to succeed in getting two to write her story. When she went public, I also went public, and I got way more coverage than she did because of the First Amendment issue.

It goes without saying that I became angry about her actions because the “facts” as told by her were incorrect. I was faced with one of two decisions: either slink away silently and live in fear, shame, and embarrassment of the protective order…or speak out and fight back, and tell my story.

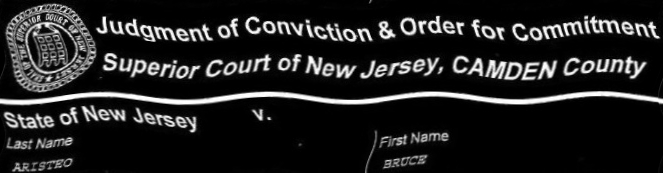

An issue I see is that people let little pieces of paper define them, such as high school diplomas, college degrees, technical and professional certifications, their financial statements, their marriage certificate, etc. A basic protective/restraining order is simply a piece of paper that formally instructs someone to stay away and not bother someone. It is a civil issue, not a criminal one. But accusers like to try to criminalize the matter. My accuser loves to do the “stalkie-talkie” routine and likes to refer to me as her “stalker.” I have called her a copyright extortionist even longer. And yet, we have never met, spoken, emailed, text-messaged, snail-mailed, or even faxed. There has never been any contact. Still, she wants to say I am a “stalker” because she currently has a little piece of paper that says “stalking protective order.”

She is attempting to define who I am to whomever will listen. The problem she has is that I don’t buy into it; I have no guilt or shame over it, and I don’t hide from it. And because I am pretty good at explaining the facts of my case and position, only the most gullible or uninformed believe her.

She is attempting to define who I am to whomever will listen. The problem she has is that I don’t buy into it; I have no guilt or shame over it, and I don’t hide from it. And because I am pretty good at explaining the facts of my case and position, only the most gullible or uninformed believe her.

Too many people take things too literally. Too many people are legally ignorant. Too many people do not understand how the judicial system works. Too many people do not understand the realities of the judicial system.

For example, I live in a city where there are overcrowded jails. I don’t think that is unique to the city I live in. I also live in a city where the district attorney and prosecutor’s office has many cases to pursue and a tight budget to do it with. I live in a city where there is an abundance of physical and “harder” crimes such as burglaries, robberies, murders, drug crimes, rapes, etc. In that context, I see the matter of a protective/restraining order (a civil matter) as ranking low in the prosecutorial pecking order.

Generally speaking, protective/restraining orders are designed to prohibit unwanted physical contact and unwanted communications. In my view, unless you have some huge emotional issues or obsessive tendencies towards your accuser, most orders are easy to follow, and they are not unconstitutional.

However, what if you have a restriction on your free speech where you can’t breathe a word about your accuser to anyone? It is certainly problematic on the local level, but it is even more problematic at a state or national level. It is simply unconstitutional, which is my way of saying that it is, in a sense, “illegal.” But some of you might say, what the order says goes. I don’t necessarily agree with that, because illegal contracts are not enforceable. For example, two people agree to do a drug deal. If one person decides to break the rules of the deal, it is unenforceable, because the deal was illegal to begin with. Likewise, an agreement broken by a John to pay a prostitute is unenforceable because it was illegal from the start. I similarly view it as illegal for my accuser to try to have me arrested or fined because I spoke or wrote about her (not to her) on my own website, and I think it would be embarrassing for any public official to dare to find me in violation of the law. That is my truth because I know what I know, but it may not be enough for you.

The sense of right and wrong has to be weighed against the costs of being a silent victim. The ability to overcome fear and ignorance, personal resourcefulness, the urgency to right a wrong, the fortitude to face conflict and risk—these are factors, and they are ones each person must self-assess.

It all begins with introspection and evaluation of whether the fight is “worth it.” In my case, if I had received a “stay away” order for one year, I would have been angry and unhappy, but I probably would never have appealed the order placed upon me. To me, it would have been an easy order to comply with, and I would not have seen it as devastating to my reputation, even if it were made public. The reason is that I know how to tell my story (and I have many times) in an open and authentic way. Certainly, there are some less than flattering reports about me but none worse than what I have seen about others.

I have a larger view of myself in this world. I am not famous, and most people don’t care about me or what I do. I am largely unimportant (to them). I am not a celebrity; I am one of many. But for many, because it happens to them, they think the whole world is actually looking at them and their restraining orders. The truth of the matter is that most people simply don’t care.

I have a larger view of myself in this world. I am not famous, and most people don’t care about me or what I do. I am largely unimportant (to them). I am not a celebrity; I am one of many. But for many, because it happens to them, they think the whole world is actually looking at them and their restraining orders. The truth of the matter is that most people simply don’t care.

In the larger view, famous people have committed all kinds of indiscretions, including having affairs, divorcing, getting into fights, committing DUI’s, doing drugs, getting arrested, soliciting prostitutes, etc. There is a huge list of all the embarrassing things people get themselves into. But the fact of the matter is most of that is small potatoes in the big scheme of things. You think people will shun and hate you, but the reality is, to most, it is trivial. You are just another person who allegedly committed an indiscretion.

You may ask, if I believe it is all small potatoes, why am I fighting so hard against my protective order? There are actually multiple reasons for my current course of action.

My accuser inflamed me. For a woman who is so allegedly afraid of me and my alleged “stalking,” her actions betrayed that she really wasn’t that frightened of me or about whether I would actually cause her any physical harm or endanger her personal safety. She chose to flaunt, brag, and gloat over her “win,” and there was no good purpose in that.

The lawyer who represented her, Elizabeth W. McBride, engaged in unethical tactics like not providing me with a copy of her exhibits so I could examine them closely, while I, a non-lawyer, gave her the professional courtesy of providing an extra copy of mine. When the hearing was over, I both called and emailed the lawyer about getting a preview copy of the protective order. I also wanted to coordinate with her about both of us getting a copy of the courtroom transcript, because it was a shared resource that was agreed upon at the beginning of my hearing. I realized she treated me the way she did because I was not a lawyer and she was trying to cheat me. Because I was opposing counsel, she was required to interact with me on certain matters as she would with another lawyer. She chose not to, and I have remembered this the last two years. One day, I am confident it will come back to bite her.

But the biggest reason I fought back was the outrage that I and others felt that there was a flagrant disregard of the First Amendment as it related to online speech, a total disregard of the actual context of my speech, and a total disregard for Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which states that website owners are not responsible for content other users post. These were all points I clearly argued but the judge seemingly ignored.

I saw this as serious misbehavior by the judge and the local court system that could potentially have wide-ranging and long-term consequences to me and any other Georgia website owner. As a matter of disclosure, I do place a great importance on my Internet presence and online activities to my business and reputation. I am a self-employed entrepreneur and business owner who regards the Internet as a hugely important resource to both his personal and business life—probably much more so than the average person who works at a job 40 hours per week for an employer.

For all those reasons, I fought back. But I would be lying if I said there weren’t moments when I wavered. I had moments of weakness, but I also had my anger to prop me up. A lot of my impetus owes to the actions of my adversary and her lawyers. By their actions, they practically taunted and drove me into appealing the case. Because of my anger and sense of injustice, I was galvanized into action.

I want to take the time to point out an important element of my fight-back. It is very helpful to find friends and supporters who understand you, your character, and the type of person you are. Getting moral support from people who will empower and encourage you is motivating. Having “support” from people who are fearful, bashful, risk-averse, cynical, and unwilling is not.

I want to take the time to point out an important element of my fight-back. It is very helpful to find friends and supporters who understand you, your character, and the type of person you are. Getting moral support from people who will empower and encourage you is motivating. Having “support” from people who are fearful, bashful, risk-averse, cynical, and unwilling is not.

In my life, I believe “like attracts like” and “birds of a feather flock together.” In my case, I have many people around me, people who are independent-minded, self-determined, believe in fighting for a cause (such as free speech) and not letting your enemies get the best of you. And believe it or not, most of my best support actually comes from those I have never met in “real life.” My best support came from “strangers” I have met on the Internet. I have never met or spoken to Todd of ROA and yet, unbeknownst to him, his work on ROA has had a huge influence on my fight.

There are so many layers to the conversation of how to fight back against a wrongful restraining order restricting your right to free speech. There is no way I could get into all the stories, tactics, and strategies, or the mindset involved in my own journey. I will one day write a book on the subject. However, as a guest blogger on ROA, I thought I would share some insights into how my mind works and the mindset that drives me.

I consider myself a victim of protective/restraining order abuse, but I have also chosen to publicly fight back against my accuser and the lower court that allowed the unconstitutional order. Win, lose, or draw, I have no regrets, because my voice is loud and travels far. And I will never let my accuser, a judge, a court, or a piece of paper define who I am. Not as long as I live.

It is that attitude, which has resonated outwards, that I believe helped attract many supporters to my side, including the lawyers who have worked on my (and my position’s) behalf.

Matthew S. Chan is the creator and administrator of ExtortionLetterInfo.com (ELI) and the appellant in Chan v. Ellis, an appeal of a lifetime protection order presently under deliberation by the Georgia Supreme Court.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com and Matthew S. Chan

*Update: The Georgia Supreme Court returned a verdict in favor of Matthew Chan on March 27, 2015.

If procedural abuses are epidemic (and they are), why do so few vociferously complain? Why isn’t the Internet inundated with personal horror stories (and why aren’t state representatives’ in-boxes choked with them)? We purportedly enjoy the

If procedural abuses are epidemic (and they are), why do so few vociferously complain? Why isn’t the Internet inundated with personal horror stories (and why aren’t state representatives’ in-boxes choked with them)? We purportedly enjoy the

A woman I’m in correspondence with and have written about was accused of abuse on a petition for a protection order last year by a scheming long-term domestic partner, a man who’d seemingly been thrilled by the prospect of publicly ruining her and having her tossed to the curb with nothing but the clothes on her back. He probably woke up each morning to find his pillow saturated with drool.

A woman I’m in correspondence with and have written about was accused of abuse on a petition for a protection order last year by a scheming long-term domestic partner, a man who’d seemingly been thrilled by the prospect of publicly ruining her and having her tossed to the curb with nothing but the clothes on her back. He probably woke up each morning to find his pillow saturated with drool. Now her former boyfriend complains that the stir she’s caused by expressing her outrage in public media is affecting his business, and he reportedly wants to obtain a restraining order to shut her up…for exposing his last attempt to get a restraining order…which was based on fraud.

Now her former boyfriend complains that the stir she’s caused by expressing her outrage in public media is affecting his business, and he reportedly wants to obtain a restraining order to shut her up…for exposing his last attempt to get a restraining order…which was based on fraud.

About a person is okay; to a person may not be.

About a person is okay; to a person may not be.

But what then can you do about it? The easy, copout answer is hire a good lawyer. But we all know “pro se” parties represent themselves because they either can’t find a good lawyer or they can’t afford a good lawyer.

But what then can you do about it? The easy, copout answer is hire a good lawyer. But we all know “pro se” parties represent themselves because they either can’t find a good lawyer or they can’t afford a good lawyer. She is attempting to define who I am to whomever will listen. The problem she has is that I don’t buy into it; I have no guilt or shame over it, and I don’t hide from it. And because I am pretty good at explaining the facts of my case and position, only the most gullible or uninformed believe her.

She is attempting to define who I am to whomever will listen. The problem she has is that I don’t buy into it; I have no guilt or shame over it, and I don’t hide from it. And because I am pretty good at explaining the facts of my case and position, only the most gullible or uninformed believe her. I have a larger view of myself in this world. I am not famous, and most people don’t care about me or what I do. I am largely unimportant (to them). I am not a celebrity; I am one of many. But for many, because it happens to them, they think the whole world is actually looking at them and their restraining orders. The truth of the matter is that most people simply don’t care.

I have a larger view of myself in this world. I am not famous, and most people don’t care about me or what I do. I am largely unimportant (to them). I am not a celebrity; I am one of many. But for many, because it happens to them, they think the whole world is actually looking at them and their restraining orders. The truth of the matter is that most people simply don’t care. I want to take the time to point out an important element of my fight-back. It is very helpful to find friends and supporters who understand you, your character, and the type of person you are. Getting moral support from people who will empower and encourage you is motivating. Having “support” from people who are fearful, bashful, risk-averse, cynical, and unwilling is not.

I want to take the time to point out an important element of my fight-back. It is very helpful to find friends and supporters who understand you, your character, and the type of person you are. Getting moral support from people who will empower and encourage you is motivating. Having “support” from people who are fearful, bashful, risk-averse, cynical, and unwilling is not.