Everyone angered by procedural abuse has a different grievance: false allegations of domestic violence, civil rights violations, wrongful claims of child abuse, exploitation of process to silence critics, and even lying about rape, to name a few. Typically, it’s what sort of procedural abuse a person has experienced—or someone close to that person has experienced—that determines the particular subject of his or her outrage. (Restraining order abuse—the abuse of court injunctions—is associated with all of them, and is often discounted as merely incidental to a “bigger problem.”)

There are some broader categories of offense, for example, hyped claims of abuse by women (of whatever nature). Prominent female advocates against procedural abuse, like Wendy McElroy, Christina Hoff Sommers, and Cathy Young, often take aim at social science that’s negatively skewed against men and blame prevailing prejudices promulgated and reinforced by what’s loosely called “mainstream feminism.” These prejudices have conditioned how accusations of abuse are treated by employers, university administrators, the police, and judges—and how they’re reflexively perceived by the public at large. Then there are First Amendment advocates who catalog and decry a plethora of misapplications of law to speech, which may be silenced by wrongful accusations of “abuse” (including violence), “harassment,” “(cyber)stalking,” “defamation,” “copyright infringement,” “trademark infringement,” etc. There’s a dominant tendency among trial court judges to pay heed to anyone who alleges something “unwanted” has been said about him or her or his or her business, especially on the Internet, which to many judges is still a suspect medium.

The success of procedural abuse boils down to a basic corruption of ethics and perception: The customer (the complainant) is always right; s/he is a “victim,” not an “accuser” or even just a “plaintiff”: a “victim.”

This characterization is inscribed in state statutes and, as a matter of form, used by prosecutors and judges in court. Even the “free press” may use it instead of “alleged victim,” and that says everything. It means there are no objective influential voices. Both judges’ and journalists’ determinations conform to a script.

People who falsely accuse seldom or never risk punishment; accountability is almost nil. The only party in jeopardy is the accused. For that reason alone, skepticism by arbiters of fact is mandated by morality.

A judge once told this writer that he considered his court the “last bastion of civilization.” Consider the implications if that supposed bulwark against societal anomie is just a puppet stage where players are issued halos and black waxed mustaches depending on which of them was first up the courthouse steps.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

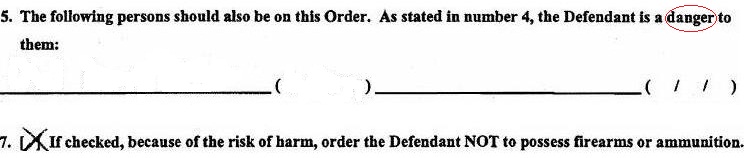

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

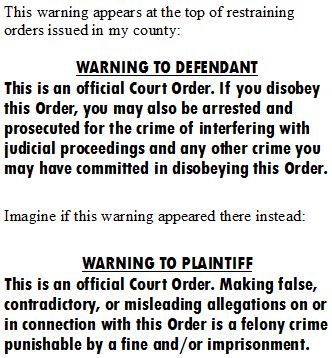

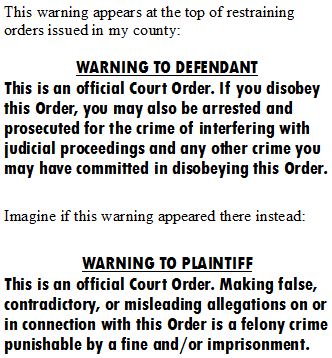

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.