I’ve had occasion in the last few months to scrutinize my own state’s (Arizona’s) restraining order statutes, which are a study in prejudice, civil rights compromises, and politically coerced naïvety. Their outdated perspective fails even to acknowledge the possibility of misuse let alone recognize the need for remedial actions to undo it.

Restraining orders are issued upon presumptive conclusions (conclusions made without judges ever even knowing who recipients are—to the judges, recipients are just names inked on boilerplate forms), and the laws that authorize these presumptive conclusions likewise presume that restraining order applicants’ motives and allegations are legitimate, that is, that they’re not lying or otherwise acting with malicious intent.

That, you might note, is a lot of presuming.

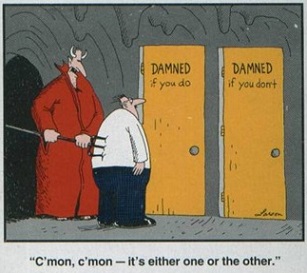

In criminal law, the state must presume that defendants are innocent; in civil law (restraining orders are civil instruments), defendants may be presumed guilty. What’s outrageous about this with respect to restraining orders is that public allegations made on them may be criminal or criminal in nature, and violations of restraining orders—real or falsely alleged—have criminal consequences. Due process and the presumption of innocence are circumvented entirely; and with these safeguards out of the way, a defendant may be jailed on no valid evidence or for doing something that’s only illegal because a judge issued a restraining order on false grounds that made it so. (A parent who’s under a court-ordered injunction may be jailed, for example, for sending his child a birthday present.)

One of my motives for consulting my state’s restraining order statutes is having absorbed a broad array of stories of restraining order abuse over the past two years. Common themes among these stories are judicial bias; lying and fraud by plaintiffs (applicants); restraining order plaintiffs’ calling, emailing, or texting the people they’ve petitioned restraining orders against (or showing up at their homes or places of work—or following them); and restraining orders’ being serially applied for by plaintiffs whose past orders have been repeatedly dismissed (that is, restraining orders’ being used to harass and torment with impunity).

Those who’ve shared their stories want to know how these abuses are possible and what, if anything, they can do to gain relief from them. The answer to the question of how lies within the laws themselves, which are flawed; the answer to the question of what to do about it may well lie outside of legal bounds entirely, which fact loudly declaims just how terribly flawed those laws are.

Arizona restraining orders are of two sorts, called respectively “injunctions against harassment” and “orders of protection.” They’re defined differently, but the same allegations may be used to obtain either. Most of the excerpted clauses below are drawn directly from Arizona’s protection order statute. Overlap with its sister statute is significant, however, and which order is entered simply depends on whether the plaintiff and defendant are relatives or cohabitants or not.

“[If a court issues an order of protection, the court may do any of the following:] Grant one party the use and exclusive possession of the parties’ residence on a showing that there is reasonable cause to believe that physical harm may otherwise result.”

This means that if your wife/husband or girlfriend/boyfriend alleges you’re dangerous, you may be forcibly evicted from your home (even if you’re the owner of that home). The latitude for satisfying the “reasonable cause” provision is broad and purely discretionary. “Reasonable cause” may be found on nothing more real than the plaintiff’s being persuasive (or having filled out the application right).

“If the other party is accompanied by a law enforcement officer, the other party may return to the residence on one occasion to retrieve belongings.”

This means you can slink back to your house once, with a police officer hovering over your shoulder, to collect a change of socks. Even this opportunity to recover some basic essentials may be denied defendants in other jurisdictions.

“[If a court issues an order of protection, the court may do any of the following:] Restrain the defendant from contacting the plaintiff or other specifically designated persons and from coming near the residence, place of employment or school of the plaintiff or other specifically designated locations or persons on a showing that there is reasonable cause to believe that physical harm may otherwise result.”

This means defendants can be denied access to their children (so-called “specifically designated persons”) based on allegations of danger that may be false.

“[If a court issues an order of protection, the court may do any of the following:] Grant the petitioner the exclusive care, custody or control of any animal that is owned, possessed, leased, kept or held by the petitioner, the respondent or a minor child residing in the residence or household of the petitioner or the respondent, and order the respondent to stay away from the animal and forbid the respondent from taking, transferring, encumbering, concealing, committing an act of cruelty or neglect in violation of section 13-2910 or otherwise disposing of the animal.”

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

Note that the linguistic presumption in all of these clauses is that recipients of restraining orders are wife-batterers, child-beaters, and torturers of puppies, and recall that restraining orders are issued without judges’ even knowing what defendants look like. This is because restraining orders were originally conceived as a deterrent to domestic violence (which, relative to the vast numbers of restraining orders issued each year, is only rarely alleged on them today at all). It’s no wonder then that judicial presumption of defendants’ guilt may be correspondently harsh. Nor is it any wonder that in any number of jurisdictions, an order of protection can be had by a plaintiff’s alleging nothing more substantive than “I’m afraid” (on which basis a judge is authorized to conclude that a defendant is a “credible threat”).

“A peace officer, with or without a warrant, may arrest a person if the peace officer has probable cause to believe that the person has violated section 13-2810 by disobeying or resisting an order that is issued in any jurisdiction in this state pursuant to this section, whether or not such violation occurred in the presence of the officer.”

This means you can be arrested and jailed based on nothing more certain than the plaintiff’s word that a violation of a court order was committed. More than one respondent to this blog has reported being arrested and jailed for a lengthy period on fraudulent allegations. Some, unsurprisingly, have lost their jobs as a consequence (on top of being denied home, money, and property).

“There is no statutory limit on the number of petitions for protective orders that a plaintiff may file.”

This observation, drawn from Arizona’s Domestic Violence Civil Benchbook, means there’s no restriction on the number of restraining orders a single plaintiff may petition, which means a single plaintiff may continuously reapply for restraining orders even upon previous applications’ having been denied.

Renewing already granted orders (which may have been false to begin with) requires no new evidence at all. Reapplying after prior applications have been denied just requires that the grounds for the latest application be different, which is of course no impediment if those grounds are made up. As search terms like this one reveal, the same sort of harassment can be accomplished by false allegations to the police: “boyfriends ex keeps calling police with false allegations.” Unscrupulous plaintiffs can perpetually harass targets of their wrath this way—and do.

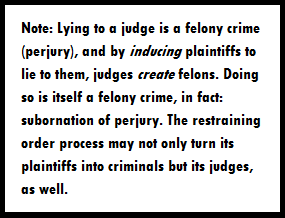

No restrictions whatever are placed upon plaintiffs’ actions, which means that they’re free to bait, taunt, entrap, or stalk defendants on restraining orders they’ve successfully petitioned with impunity. And neither false allegations to the police nor false allegations to the courts (felony perjury) are ever prosecuted.

“A fee shall not be charged for filing a petition under this section or for service of process.”

This means the process is entirely free of charge.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers ever get their just deserts.

Many restraining order recipients are brought to this site wondering how to recover damages for false allegations and the torments and losses that result from them. Not only is perjury (lying to the court) never prosecuted; it’s never explicitly acknowledged. The question arises whether false accusers ever get their just deserts.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

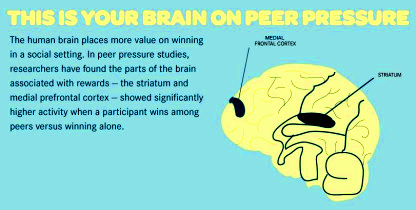

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?

I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible? One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that.

One of the aforementioned teachers was on his way to Nashville to become a songwriter, that is, a creative artist. Any career in the public eye like this one is vulnerable to being compromised or trashed by a scandal that may be based on nothing but cunning lies or a disturbed person’s fantasies spewed impulsively in a window of five or 10 minutes. Besides the obvious impairment that something like this can exert on income prospects, its psychological effects alone can make performance of a job impossible. And nothing kills income prospects more surely than that. Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child.

The answer to these questions is of course known to (besides men) any number of women who’ve been victimized by the restraining order process. They’re not politicians, though. Or members of the ivory-tower club that determines the course of what we call mainstream feminism. They’re just the people who actually know what they’re talking about, because they’ve been broken by the state like butterflies pinned to a board and slowly vivisected with a nickel by a sadistic child. Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret.

Many of the respondents to this blog are the victims of collisions like this. Some anomalous moral zero latched onto them, duped them, exploited them, even assaulted them and then turned the table and misrepresented them to the police and the courts as a stalker, harasser, or brute to compound the injury. Maybe for kicks, maybe for “payback,” maybe to cover his or her tread marks, maybe to get fresh attention at his or her victim’s expense, or maybe for no motive a normal mind can hope to accurately interpret. The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge). I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation.

I came upon a monograph recently that articulates various motives for the commission of fraud, including to bolster an offender’s ego or sense of personal agency, to dominate and/or humiliate his or her victim, to contain a threat to his or her continued goal attainment, or to otherwise exert control over a situation. The narcissist has a distorted sense of his or her own self-worth, distorts perceived slights or criticisms into monstrous proportions, and endeavors to distort others’ perceptions of those who dared to “criticize.”

The narcissist has a distorted sense of his or her own self-worth, distorts perceived slights or criticisms into monstrous proportions, and endeavors to distort others’ perceptions of those who dared to “criticize.” The outrage of

The outrage of

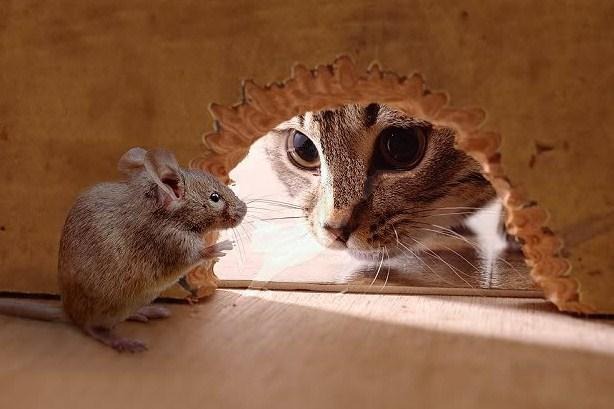

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog).

Because restraining orders place no limitations on the actions of their plaintiffs (that is, their applicants), stalkers who successfully petition for restraining orders (which are easily had by fraud) may follow their targets around; call, text, or email them; or show up at their homes or places of work with no fear of rejection or repercussion. In fact, any acts to drive them off may be represented to authorities as violations of those stalkers’ restraining orders. It’s very conceivable that a stalker could even assault his or her victim with complete impunity, representing the act of violence as self-defense (and at least one such victim of assault has been brought to this blog). Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).

Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone). What this blog and

What this blog and  That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled  Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

The

The  Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called

Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called  The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better.

The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better. The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?

The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?

Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied

Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied  This question pops up a lot.

This question pops up a lot.