“The consequences that arise once a protective order is entered against a person (the respondent) are substantial. Though technically considered civil proceedings, protective orders have a close relationship to criminal law. The consequences of having a protective order entered often include restrictions on constitutional rights in addition to financial obligations. Violations of protective orders bring about serious criminal charges.”

“I have been fighting for 10 years to clear my son’s name from a false restraining order that [was] dismissed and vacated by the court. But to clear themselves, [officers of] the judicial system turn their heads to the wrongdoing and cause this young man to be [defamed], not able to continue his education, etc. His [access to] life has, it seems like, forever been barred.”

The remark above by a criminal lawyer on the “consequences of protective orders” echoes those of many other attorneys (which may observe that restraining order records limit job opportunities and can interfere with the lease of a home, getting government housing, or obtaining credit). I could find you a quotation along the same lines from a law firm in any state of the Union. The woman whose remark follows the lawyer’s, Lena Bennett, identifies herself as a “concerned mother who needs to be heard,” and this post is dedicated to her and her son.

A former trial attorney, Larry Smith, who knows the law in this arena better than he wishes he did, responded to Lena: “I doubt that you can get an expired order expunged in most states because the restraining order, although it has may components of the criminal law, is said to be civil.”

A former trial attorney, Larry Smith, who knows the law in this arena better than he wishes he did, responded to Lena: “I doubt that you can get an expired order expunged in most states because the restraining order, although it has may components of the criminal law, is said to be civil.”

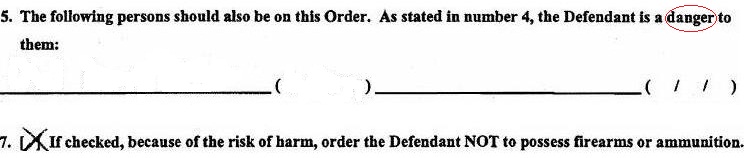

As usual, Larry gets right to the heart of the matter. The fact is there are laws on the books that allow a person who’s been convicted in a criminal court of, say, harassment, stalking, terroristic threats, or assault to later have the charges expunged.

But if a person is baselessly accused of any or all of these acts on a civil restraining order, there’s no legislation in place (except in Tennessee) to enable him or her to have the accusations removed from his or her public record even if a judge determined them to be baseless and dismissed the order.

Note: People who have actually committed crimes can relieve themselves of the onus of a court record (that may hobble their employment opportunities), while people who’ve merely been accused on an ex parte order of the court (30 minutes in and out) are incriminated for life without ever having been tried for a crime, and that, again, is even if a judge formally decreed them innocent and tossed the accusations.

The paper trail, which may include multiple false reports to police officers and registration in police and publicly accessible state databases, is indefinitely preserved.

(Let’s say you’re an employer screening a male job applicant, and you see a restraining order record on which a woman has indicated that he stalked or sexually assaulted her. Let’s even say the court dismissed the case as lacking any foundation. Will you or won’t you be influenced by that record?)

Excuses for preserving restraining order records, which emerge from anti-domestic-violence dogmatists, are anachronistic. Typical of the law, statutes are about 20 years behind social trends.

Consider:

The bill whose defeat is reported in the headline above would have allowed citizens of Maryland who had been accused of domestic violence on a dismissed restraining order petition to have the allegations completely expunged (erased). It was shot down.

Supporters of the measure argued that abuse accusations carry such a stigma that allowing records to remain public in cases that have been deemed unfounded unfairly hurts innocent people as they seek employment or housing.

Opponents contended that requests for protective orders are often dismissed because battered victims, usually women, are too scared or intimidated to pursue the matter. They said records are not expunged in other kinds of civil cases, even when allegations are unproved.

Never mind that these opponents are well aware that restraining order cases are not like “other kinds of civil cases.” Their implications are plainly criminal and highly prejudicial. They’re recorded in police databases.

A year later, another bill is proposed to the same legislature. This one wouldn’t expunge anything, but it would “hide” restraining order records from public view.

A year later, another bill is proposed to the same legislature. This one wouldn’t expunge anything, but it would “hide” restraining order records from public view.

“Shielding” is possible in Maryland today and only requires a clerk to sign off on it. It removes the record of a dismissed order from Maryland’s Judiciary Case Search. The record still exists, however, and can be easily accessed by anyone who swings by the courthouse.

In the whole of the nation, as revealed by a Google search performed yesterday, these are the only states in which there are reportedly means to have a restraining order expunged:

Of these, only Tennessee has an actual statute (law) enabling a person who’s been accused on a restraining order petition that was later dismissed to move the court to expunge the record.

And in only a handful of states (again, according to a casual Google search) has legislation been proposed that would offer the same opportunity to their citizens:

That’s it.

Copyright © 2016 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

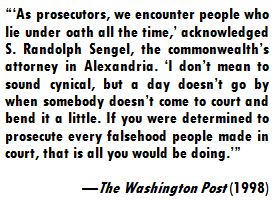

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

With regard to the honest representation of facts in court, however, both accusers and judges fudge (and that’s putting it mildly). Each may frame facts to produce a favored impression.

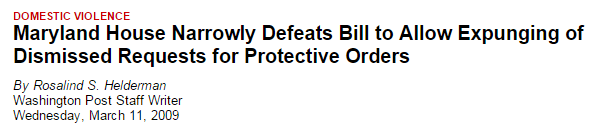

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations).

People falsely alleged to be abusers on restraining order petitions, particularly men, are treated like brutes, sex offenders, and scum by officers of the court and its staff, besides by authorities and any number of others. Some report their own relatives remain suspicious—often based merely on finger-pointing that’s validated by some judge in a few-minute procedure (and that’s when relatives aren’t the ones making the false allegations). So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

So…slanders and libels made by abuse of court process aren’t actionable, slanders and libels that completely sunder the lives of the wrongly accused, who can’t even get them expunged from their records to simply reset their fractured lives to zero.

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”: Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else.

Scholars, members of the clergy, and practitioners of disciplines like medicine, science, and the law, among others from whom we expect scrupulous truthfulness and a contempt for deception, are furthermore no more above lying (or actively or passively abetting fraud) than anyone else. M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

M.D., Ph.D., Th.D., LL.D.—no one is above lying, and the fact is the better a liar’s credentials are, the more ably s/he expects to and can pull the wool over the eyes of judges, because in the political arena judges occupy, titles carry weight: might makes right.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified.

I understand her very well, but at the risk of pointing out the obvious, she shouldn’t have to. False allegations aren’t a withered limb, a ruptured disc, or an autoimmune disease. These latter things are real and unavoidable. Lies aren’t real, and their pain is easily relieved. The lies just have to be rectified. The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary.

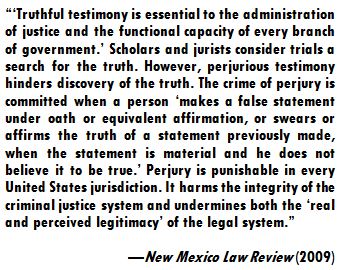

The restraining order process has become a perfunctory routine verging on a skit, a scripted pas de deux between a judge and a complainant. Exposure of the iniquity of this procedural farce hardly requires commentary. The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge). The narcissist has a distorted sense of his or her own self-worth, distorts perceived slights or criticisms into monstrous proportions, and endeavors to distort others’ perceptions of those who dared to “criticize.”

The narcissist has a distorted sense of his or her own self-worth, distorts perceived slights or criticisms into monstrous proportions, and endeavors to distort others’ perceptions of those who dared to “criticize.”

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

I’ve recently tried to debunk some of the

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

What most people don’t get about restraining orders is how much they have in common with Mad Libs. You know, that party game where you fill in random nouns, verbs, and modifiers to concoct a zany story? What petitioners fill in the blanks on restraining order applications with is typically more deliberate but may be no less farcical.

I this week came across an online monograph with the unwieldy (and very British) title, “Drama Queens, Saviours, Rescuers, Feigners, and Attention-Seekers: Attention-Seeking Personality Disorders, Victim Syndrome, Insecurity, and Centre of Attention Behavior,” which pointedly speaks to a number of behaviors identified by victims of restraining orders who have written in to this blog or alternatively contacted its author concerning the plaintiffs in their cases.

I this week came across an online monograph with the unwieldy (and very British) title, “Drama Queens, Saviours, Rescuers, Feigners, and Attention-Seekers: Attention-Seeking Personality Disorders, Victim Syndrome, Insecurity, and Centre of Attention Behavior,” which pointedly speaks to a number of behaviors identified by victims of restraining orders who have written in to this blog or alternatively contacted its author concerning the plaintiffs in their cases.

A recent respondent to this blog detailed his restraining order ordeal at the hands of a woman who he persuasively alleges is a

A recent respondent to this blog detailed his restraining order ordeal at the hands of a woman who he persuasively alleges is a

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

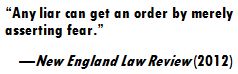

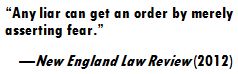

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)