In “How the Fifth Amendment Impacts Family Court in Domestic Violence Cases” (2013), family attorney Tracy Duell-Cazes offers the following counsel against self-incrimination (it’s directed to Californians but may be applicable generally):

To make this easier to read, I will use Respondent when referring to the person who is accused of committing a domestic violence offense and Petitioner for the person against whom the violence was alleged to have been committed.

The Respondent has the right not to make [self-]incriminating statements in any proceeding. This includes discovery, hearings, and any other place where statements may be made. The general rule is that the Respondent cannot be required to testify at the restraining order hearing. The Respondent does not have to produce any discovery regarding the domestic violence issue if the Respondent timely claims the privilege against self-incrimination in response to the discovery request.

The Respondent has the right not to make [self-]incriminating statements in any proceeding. This includes discovery, hearings, and any other place where statements may be made. The general rule is that the Respondent cannot be required to testify at the restraining order hearing. The Respondent does not have to produce any discovery regarding the domestic violence issue if the Respondent timely claims the privilege against self-incrimination in response to the discovery request.

Courts usually grant a continuance until the criminal action is concluded. The temporary restraining orders stay in effect. Once the criminal action is concluded, then the hearing in Family Court can go forward. Usually the criminal case is dispositive of whether or not permanent restraining orders in Family Court are issued. If there is a conviction, the permanent restraining orders will almost always be ordered.

The Respondent must make sure that s/he doesn’t say anything to anyone but his/her attorney. (It is usually a good idea in these kinds of cases to have an attorney who practices family law and knows something about criminal law.) If any discovery is sent to you to answer, you need to assert your privilege against self-incrimination in a timely fashion. If you do not, you will lose this right and be required to testify against yourself and be required to respond to the discovery request. This means that the court can compel you to answer the questions, or sanctions will be imposed. Sanctions can be anything from your paying money to the other side to the issue being decided with only the other person’s information.

In order for [the] Respondent to give up his/her right to remain silent, s/he must knowingly and intelligently waive that right. This means that s/he has to know the consequences if s/he talks about the facts and that s/he understands that whatever s/he says can (read will) be used against her/him in the criminal case. If you are ever unsure of whether or not you have a “right to remain silent,” you should immediately consult with an attorney. It is best to consult with an attorney who practices both family law and criminal law or who handles domestic violence cases.

Copyright © 2013, 2015 Tracy Duell-Cazes and RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The Fifth Amendment guarantees you don’t have to say anything against yourself. To enjoy this privilege, however, you have to say you don’t intend to say anything against yourself (e.g., “I decline to answer on the grounds that it may tend to incriminate me”). You can’t, in other words, be completely silent. (See Ms. Duell-Cazes’s next to last paragraph above.)

I’ve written before about “

I’ve written before about “

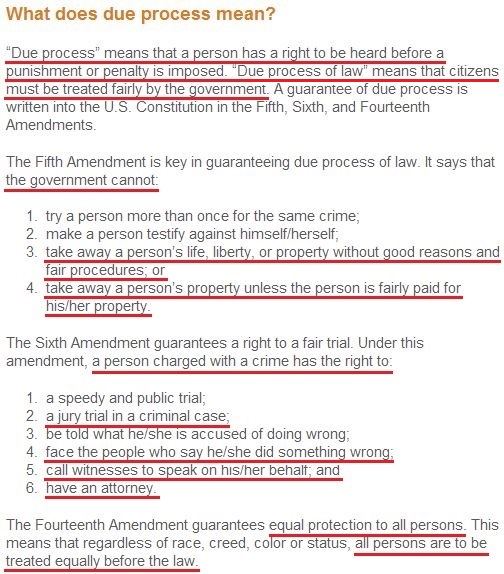

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =

A defendant is deprived of liberty and often property, besides, without compensation and in accordance with manifestly unfair procedures concluded in minutes =