“I am the victim of false accusations [by] a female with sociopathic tendencies. She stabbed my husband [and] threatened to kill me, but for whatever reason filed for a domestic violence protective order on me. I value respect from people, so I do and act morally to maintain my relationships, but because any given person, whether sane or not, can go file a petition with its being granted depending on how it’s worded, I was treated like a criminal and not one time given the opportunity to inform even the judge that the petitioner had committed perjury. Only in [West Virginia] a felony can be committed and go unpunished. This is [an overlooked] flaw that needs immediate attention!!!! This not only jeopardizes my future, but my kids’ future, because if the petitioner wouldn’t have dropped it, it would [have been] filed in a national database, popping up whenever a background check is done on me, including [by] my college for my admission into Nuclear Medicine Technology…and this is all based on a drug-addicted, manipulating, vindictive person’s false accusations.”

—Female e-petition respondent

“Dangerous law easily used as a sword instead of shield. A Butte man died over this. His girlfriend, after making the false allegations, cleaned out his bank account. He committed suicide. His mother, Ruth, had no money to bury him. The girlfriend depleted his assets partying.”

—Female e-petition respondent

“I can relate to this topic, because I once made false allegations against my lover because I was a woman scorned and wanted to get even with him and make him feel the same level of pain that he made me feel. Luckily for him and me, I was convicted in my spirit and confessed to the court that I’d lied, and the matter was dropped. If I’d not been led to do that, my lie could have ruined this man’s life….”

—Female e-petition respondent

“It makes me sick that there are so many families affected by false allegations. The children [who] are affected break my heart. We have been living this nightmare for over a year now—over $40 thousand dollars spent, and this woman still keeps us in court with her false allegations…. At what point will the courts make these people accountable???”

—Female e-petition respondent

A recent comment to this blog from a female victim of restraining order abuse (by her husband) expressed the perception that criticism of feminist motives and the restraining order process, a feminist institution of law, seemed vitriolic toward women.

Her reaction is understandable.

What isn’t perceived generally, including by female victims of fraudulent abuse of process, is that the restraining order was prompted by feminist lobbying just a few decades ago and that its manifest injustices are sustained by feminist lobbying. It’s not as though reform has never been proposed; it’s that reform is rejected by those with a political interest in preserving the status quo.

Political motives, remember, aren’t humanitarian motives; they’re power motives.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

So enculturated has the belief that women are helpless victims become that no one recognizes that feminist political might is unrivaled—unrivaled—and it’s in the interest of preserving that political might and enhancing it that the belief that women are helpless victims is vigorously promulgated by the feminist establishment that should be promoting the idea that women aren’t helpless.

It’s this belief and this political might that make restraining order abuses, including abuses that trash the lives of women, possible. Not only does the restraining order process victimize women; it denies that women have personal agency.

Nurturance of the belief that women are helpless victims puts a lot of money in a lot of hands, and very few of those hands belong to victims.

The original feminist agenda, one that’s been all but eclipsed, was inspiring women with a sense of personal empowerment and dispelling the notion that they’re helpless. The restraining order process is anti-feminist as is today’s mainstream feminist agenda, which equity feminists have been saying for decades.

Restraining orders continue to be doled out (in the millions per annum) on the basis of meeting a civil standard of evidence (which means no proof is necessary), pursuant to five- or 10-minute interviews between plaintiffs and judges, from which defendants are excluded.

So certainly has the vulnerability and helplessness of women been universally accepted that the state credits claims of danger or threat made in civil restraining order applications on reflex, including by men, because our courts must be perceived as “fair.” Consequently, fraudulent claims are both rampant and easily put over.

Restraining orders aren’t pro-equality and don’t contribute to the advancement of social justice. They do, though, put a lot of people’s kids through college, like lawyers’ and judges’.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Ignore that and consider what judge, in the “bad old days” before restraining orders existed, would have allowed a woman to be publicly labeled a rapist, merely by implication.

Ignore that and consider what judge, in the “bad old days” before restraining orders existed, would have allowed a woman to be publicly labeled a rapist, merely by implication.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it.

In fact, what it and any number of others’ ordeals show is that when you offer people an easy means to excite drama and conflict, they’ll exploit it. A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.”

A man eyes a younger, attractive woman at work every day. She’s impressed by him, also, and reciprocates his interest. They have a brief sexual relationship that, unknown to her, is actually an extramarital affair, because the man is married. The younger woman, having naïvely trusted him, is crushed when the man abruptly drops her, possibly cruelly, and she then discovers he has a wife. Maybe she openly confronts him at work. Maybe she calls or texts him. Maybe repeatedly. The man, concerned to preserve appearances and his marriage, applies for a restraining order alleging the woman is harassing him, has become fixated on him, is unhinged. As evidence, he provides phone records, possibly dating from the beginning of the affair—or pre-dating it—besides intimate texts and emails. He may also provide tokens of affection she’d given him, like a birthday card the woman signed and other romantic trifles, and represent them as unwanted or even (implicitly) disturbing. “I’m a married man, Your Honor,” he testifies, admitting nothing, “and this woman’s conduct is threatening my marriage, besides my status at work.” Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive.

Those who profit politically and monetarily by the misery inflicted through court processes that are easily abused by the “morally unencumbered” love all this conflict and misdirected rage, which only ensure that these corrupt processes continue to thrive. What this blog and

What this blog and  I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused.

I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused. Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male.

Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male. As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

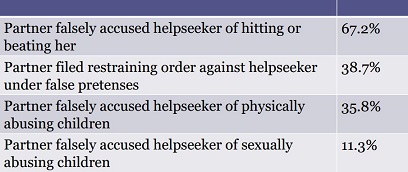

Dr. Charles Corry, president of the

Dr. Charles Corry, president of the

So how is it so many men are railroaded through a process that may be initiated on no evidence at all, may strip them of their most valued investments and every bit of social and financial equity they’ve built in their lives—kids, home, money, property, business, and reputation—and may ensure that they’re never able to recover what they’ve been deprived of?

So how is it so many men are railroaded through a process that may be initiated on no evidence at all, may strip them of their most valued investments and every bit of social and financial equity they’ve built in their lives—kids, home, money, property, business, and reputation—and may ensure that they’re never able to recover what they’ve been deprived of?

It shouldn’t be any mystery why with millions of restraining orders being issued each year in the Internet age complaints of abuses aren’t louder and more numerous: stigma.

It shouldn’t be any mystery why with millions of restraining orders being issued each year in the Internet age complaints of abuses aren’t louder and more numerous: stigma.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do.

A person who obtains a fraudulent restraining order or otherwise abuses the system to bring you down with false allegations does so because you didn’t bend to his or her will like you were supposed to do. The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

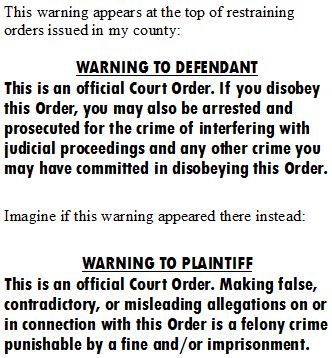

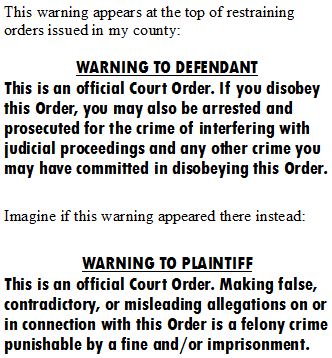

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.