“The First Amendment is FIRST for a reason.”

—Larry Smith, former attorney and indomitable muckraker

A recent post on this blog revisited the case of Matthew Chan, author of ExtortionLetterInfo.com (ELI), whose appeal of a lifetime restraining order is presently under consideration by the Georgia Supreme Court. A verdict is anticipated within the coming month or months.

Criticisms are handily represented as acts of terrorism to the courts, whose officers have been conditioned to pander to accusers. Anyone is a potential target of facile accusations, which are made in mere moments. Retirees and vegetarian soccer moms, for whom the cost of attorney representation is often prohibitive, report being implicated as violent menaces and tyrants.

This post reports a successful appeal waged by North Carolinian Cindie Harman, who was issued a no-contact order for allegedly “cyber-stalking” a mother and her minor daughter by publicly criticizing them in a blog. Mrs. Harman named the adult plaintiff’s daughter a “bully” of other children and opined that her behavior was influenced by her mother’s conduct.

According to the Associated Press, the mother, who owns or owned an Asheville-area water services company, was “sentenced to nearly three years in prison for faking thousands of tests designed to ensure that drinking water is safe” in 2012 (and also faced “conspiracy charges”), had “plead guilty in 2010 to mail fraud,” and “paid a fine and did community service after pleading guilty to misconduct by a public official after she was charged with embezzling more than $10,000 from Marshal when she served as town clerk there.” Mrs. Harman’s accuser, whose husband is a former magistrate, controverts the popular notion that restraining order applicants are innocent lambs seeking protection from marauding predators.

Mrs. Harman prevailed in her restraining order appeal, but the vindication of her character and her judgment of her accuser’s character didn’t come without a steep price—and that’s excluding attorney fees.

According to the blogger quoted in the epigraph, Larry Smith, a friend of Mrs. Harman’s and fellow comrade-in-arms:

During the long time this case was pending, I had been talking to Cindie on the telephone, trying to reassure her that she would win her case in the NC Court of Appeals. She was very nervous, inconsolable, dyspeptic, upset about it.

Being accused of stalking, let alone being accused of stalking a child, isn’t funny. It’s the kind of thing that breaks a person.

To be charged with stalking in North Carolina signifies you’ve caused someone “to suffer substantial emotional distress by placing that person in fear of death, bodily injury, or continued harassment.” (Note that the latter element of the statutory definition of stalking, “continued harassment,” is glaringly incongruous to the elements that precede it. The contrast between fear of “death [or] bodily injury” and fear of “continued harassment” underscores the slapdash, catch-all nature of stalking and related statutes that makes them not only objectionable but outrageous, and urges their legislative revision or repeal.)

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added).

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added).

Observe that even the court’s grammar was bad. The ruling should have read “transmissions…that torment, terrorize, or terrify.” Gaffes like this are hardly surprising considering how hastily and carelessly restraining order judgments are formed.

Mrs. Harman was said to have tormented, terrorized, or terrified the child plaintiff by referring to her as a “bully” (a “reason kids hate to go to school”) and tormented, terrorized, or terrified her mother by calling her a “crow,” an “idiot,” and a “wack” on a blog.

Terrifying indeed.

At the beginning of this year, Law Professor Jonathan Turley eagerly reported that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled “Bloggers Have Same First Amendment Rights As Journalists” (cf. Robinson Meyer’s “U.S. Court: Bloggers Are Journalists,” published in The Atlantic, and “Reporters’ Privilege,” prepared by the Electronic Frontier Foundation). Judges in North Carolina seem not to have heard the news.

The decision came in a defamation lawsuit where the panel ordered a new trial in the case of Crystal L. Cox, a blogger from Eureka, Montana. Cox was sued for defamation by attorney Kevin Padrick and his company, Obsidian Finance Group LLC, after she wrote about what she viewed as fraud, corruption, money-laundering and other illegal activities.

The details may sound familiar.

In legal commentary presented in Chan v. Ellis, the appeal mentioned in the introduction to this post, Law Profs. Eugene Volokh and Aaron Caplan asserted to the Georgia Supreme Court:

The First Amendment protects the right to speak about people, so long as the speech does not fall into an established First Amendment exception (such as those for defamation or for true threats). This includes the right to speak about private figures, especially when they do something that others see—rightly or wrongly—as unethical.

Restraining orders and criminal stalking law may properly restrict unwanted speech to a person. But they may not restrict unwanted speech about a person, again unless the speech falls within a First Amendment exception. The trial court’s order thus violates the First Amendment.

This may also sound familiar.

Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect.

Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect.

Reportedly consequent to receiving threats against her person and having several of her pets poisoned, Mrs. Harman has removed her blogs. Even her Twitter feed is now “protected” and no longer accessible to a general audience. Mrs. Harman lives in the sticks and says if she weren’t armed, she’d be afraid to be alone.

She has been terrorized into silence.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The author of this blog, too, has had a lifetime injunction imposed upon him by the court for communication “about a person” (communication that alleged misconduct, including criminal, by a public official). His 2013 trial, which was conducted in the Superior Court of Arizona and in which he represented himself, concluded less than four months before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in Cox v. Obsidian Finance Group. He hasn’t subsequently received any threats but has been monitored. His accuser, a married woman he encountered standing outside of his house one day in 2005 (and many nights thereafter), is believed to be among the first to read anything posted here.

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added).

The trial court that heard the restraining order case against Mrs. Harman, and whose backroom judgment was overturned by the North Carolina Court of Appeals, had ruled, “Defendant [Harman] has harassed plaintiffs within the meaning of [N.C. Gen. Stat. §] 50C-1(6) and (7) by knowingly publishing electronic or computerized transmissions directed at plaintiffs that torments, terrorizes, or terrifies plaintiffs and serves no legitimate purpose” (italics added). Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect.

Cindie Harman ultimately won the case against her, a case that should never have been entertained by the court in the first place, but a victory that should have reassured her that freedom of speech in our country is a revered and inviolate privilege has had the opposite effect.

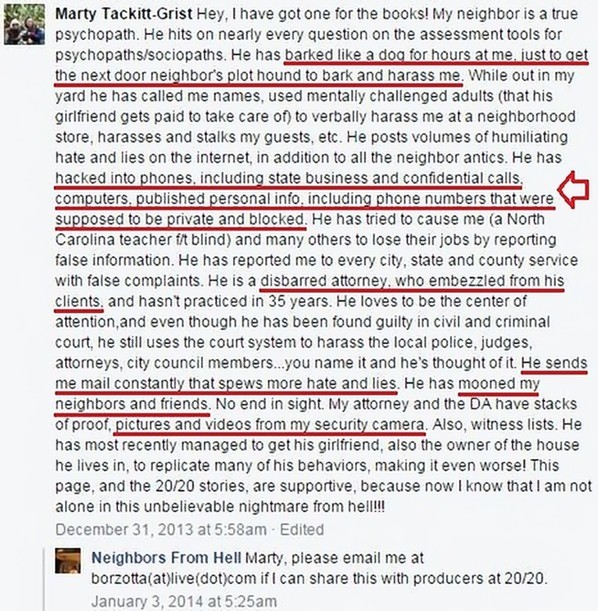

I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?

I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?