Here’s a group of women on a forum for mothers with school-aged kids responding to a conversational prompt that deserves the attention of those who believe false allegations made out of spite are rare and that the report of such allegations is overblown and only originates from father’s rights groups (or what one notable polemicist calls “FRGs”).

“Has someone ever called CPS on you out of spite? Have you called on someone? Why?”

Not surprising to this writer, a number of respondents commented in the affirmative. Also worthy of note in this context is that the site FightCPS.com is authored by a woman.

Here are a few of the topmost comments on the Circle of Moms thread:

Yes, twice I’ve had CPS called on me out of spite. Both times a social worker came to my house. I had nothing to hide, so I let them in and they both said, “I can’t tell you who called us, but I can tell you this is absolutely ludicrous for us to even come to your house, because we can’t find a single thing wrong. Sounds like a false allegation to me.” I was like, “I know, right. Thank you.” They couldn’t tell me who called, but I already knew who was behind it. The person who did it was just mad because I wouldn’t

pay them money I didn’t even owe! This person was my babysitter, who is the most manipulative, money hungry witch. I just didn’t know it until now.

[M]y mom and sister have been calling and making false accusations about me ever since I told them they’re not my children’s mom—I am. They thought they were just going to tell me how to [rear my] kids, and I told them both, sorry about your luck, I’m their mom, and that’s final. I’ve never gotten a break from CPS since. Especially because my mom didn’t raise us—we did ourselves. And then she thought she was going to take mine and my husband’s first daughter and raise her as her [own] to try to fix mistakes that couldn’t be fixed. UH-UH, she wasn’t getting my daughter. Not till she called my sick, demented sister in to plot against me for 16 years and stole my life, my soul, my heart, my babies. Don’t trust no one.

The person [who] called them on me and my two children knew my mom was very sick and did not have much time to live. My mom died four days ago. Six days before she died, CPS came out. The person who called them on me wanted to add even more pain to my life—and fear. I went and picked up the report. It said [no] on every one of the allegations. I think CPS should let you know who called so you can file a lawsuit. I mean, if they do not do anything, then we should have a choice. We should have the right to know so we can stay away from those who called on us. It should be up to us to tell CPS to press charges or let us do it ourselves, and if we do not know who did call, then we have not got the right kind of privacy or peace throughout our lives.

According to a brochure published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Children’s Bureau:

Approximately 29 States carry penalties in their civil child protection laws for any person who willfully or intentionally makes a report of child abuse or neglect that the reporter knows to be false. In New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the Virgin Islands, making false reports of child maltreatment is made illegal in criminal sections of State code.

Nineteen states and the Virgin Islands classify false reporting as a misdemeanor or similar charge. In Florida, Illinois, Tennessee, and Texas, false reporting is a felony, while in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, and Virginia, second or subsequent offenses are upgraded to felonies.

In Michigan, false reporting can be either a misdemeanor or a felony, depending on the seriousness of the alleged abuse in the report. No criminal penalties are imposed in California, Maine, Montana, Minnesota, and Nebraska; however, immunity from civil or criminal action that is provided to reporters of abuse or neglect is not extended to those who make a false report.

Eleven States and the Virgin Islands specify the penalties for making a false report. Upon conviction, the reporter can face jail terms ranging from 90 days to 5 years or fines ranging from $500 to $5,000. Florida imposes the most severe penalties: In addition to a court sentence of 5 years and $5,000, the Department of Children and Family Services may fine the reporter up to $10,000. In six States, the reporter may be civilly liable for any damages caused by the report.

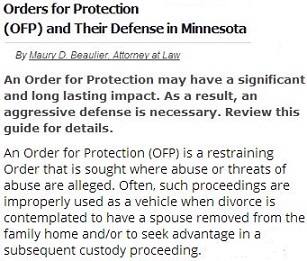

Based on the anecdotal reports in the referenced Circle of Moms thread, consider how likely it is any of the reported mischief was ever prosecuted. This kind of sniping, which is impossible to fend off, exactly corresponds to that perpetrated by abusers of the restraining order process, which is also exempted from the exacting standards of police and judicial scrutiny that are supposed to be applied when allegations have criminal overtones or can lead to serious privations or criminal consequences.

The women responding in this forum aren’t “anti-feminists,” and they’re certainly not motivated to report malicious exploitation of state process because they’re “for” child abuse: They’re moms.

Yet despite that under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), billions of dollars have been invested over the past 20 years toward conditioning authorities and the courts to take allegations of violence and abuse on faith, when fathers allege identical exploitation of restraining orders and domestic violence laws according to the spiteful motives alleged by the mothers cited in this post, they’re dismissed as cranks by feminists and their partisans.

Disinterested parties and feminist sympathizers are urged to recognize that if mothers and fathers are saying the same things, then the claim that allegations of procedural abuses are nothing more than the baseless rants of angry men is flatly wrong.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

From a draft of Ally’s “Motion to Expunge”:

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair.

Ironic is that Dr. Behre’s denial of men’s groups’ position that men aren’t treated fairly is itself unfair.

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

What isn’t appreciated by critics of various men’s rights advocacy groups is that these groups’ own criticisms are provoked by legal inequities that are inspired and reinforced by feminist groups and their socially networked loyalists. These feminist groups arrogate to themselves the championship of female causes, among them that of battered women. Feminists are the movers behind the “battered women’s movement.”

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

The professor carefully prefaces her points with phrases like “Researchers have noted,” which gives them the veneer of plausibility but ignores this obvious question: where do the loyalties of those “researchers” lie? The professor cites, for example, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s equation of SAVE Services with a hate group. An attentive survey of SAVE’s reportage, however, would suggest little correspondence. The professor doesn’t quote any of SAVE’s reports; she simply quotes an opposing group’s denunciation of them as being on a par with white supremacist propaganda.

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

Members of the legislative subcommittee referenced in The Courant article reportedly expect to improve their understanding of the flaws inherent in the restraining order process by taking a field trip. They plan “a ‘ride along’ with the representative of the state marshals on the panel…to learn more about how restraining orders are served.”

“

“ The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

The lawyers quoted by reporter, what’s more, refer to criminal cases in which sexual abuse is alleged and, consequently, in which the accused are afforded attorney representation.

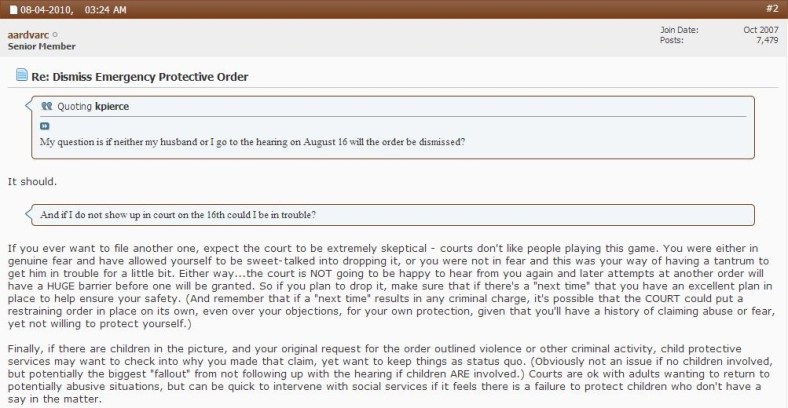

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc.

Faith in the conceit that restraining orders are minor impingements on defendants’ lives depends on accepting that being falsely, publically, and permanently labeled a stalker or batterer, for example, shouldn’t interfere with a person’s comfort, equanimity, or ability to realize his or her dreams. Such faith is founded, in other words, on the fantastical belief that wrongful vilification won’t exercise a detrimental influence on a person’s mental state, won’t affect his or her familial and social relationships, won’t negatively impact his or her employment and employability, etc. As attorneys and

As attorneys and

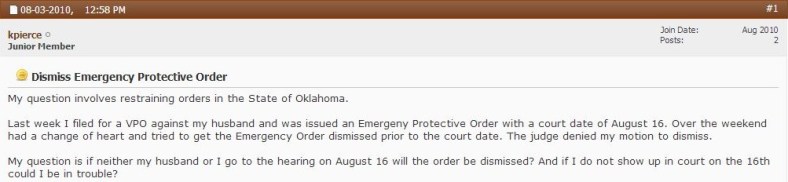

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

Notable, contrariwise, however, is that the respondent discourages the petitioner of the restraining order, who’s admitted to proceeding impulsively, from following through with her expressed intention to rectify an act that may have been motivated by spite. The respondent is the executive director of

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences.

A scratch, a push, a pinch—which may not even have been real but whose allegation had real enough consequences. I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

I’ve written recently about the abuse of restraining orders by fraudulent litigants to punish. What needs observation is that the laws themselves, that is, restraining order and domestic violence statutes, are corrupted by the same motive: to punish. Their motive is not simply to protect (a fact that’s borne out by the prosecution of alleged pinchers).

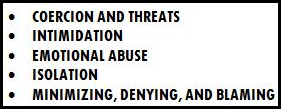

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

Noteworthy finally is Ms. Malloy’s acknowledgment that false allegations of violence, which are devastating in the emotional oppression, humiliation, and social and professional havoc they wreak on the falsely accused, are used strategically to gain leverage in divorce proceedings.

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.”

Playing the victim is a very potent form of passive aggression when the audience includes authorities and judges. Validation from these audience members is particularly gratifying to the egos of frauds, and both the police and judges have been trained to respond gallantly to the appeals of “damsels in distress.” I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?

I’ll answer for you: No, he doesn’t sound crazy or dangerous. Next question (this is how critical thinking works): If he’s telling it true, how is something like this possible?

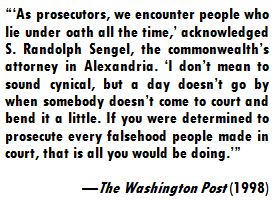

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title.

“If we did prosecute perjurers, there’d be no resources left for putting dangerous people behind bars…so we’ll prosecute the people perjurers falsely accuse of being dangerous”—as analysis of most of the arguments made in defense of domestic violence and restraining order policies reveals, the reasoning is circular and smells foul. It’s in fact unreasoned “reasoning” that’s really just something to say to distract attention from unflattering truths that don’t win elections, federal grants, popular esteem, or political favor. So entrenched are these policies and so megalithic (and lucrative) that rhetoric like this actually passes for satisfactory when it’s used by someone in a crisp suit with a crisper title. What this blog and

What this blog and