“Critics argue that reports of rape should be treated with more caution, since men’s lives are so often ruined by women’s malicious lies.

“But my research—including academic studies, journalistic accounts, and cases recorded in the US National Registry of Exonerations—suggests that every part of this narrative is wrong.”

—Sandra Newman, Quartz (May 11, 2017)

The quoted article is titled, “What kind of person makes false rape accusations?” Its URL slug, in contrast, is “the-truth-about-false-rape-accusations.” Plain from article’s slant is that its author wasn’t motivated to discover what kind of monster makes false rape accusations but rather to vindicate her conviction that false rape accusations, and false accusations generally, aren’t significant.

Having grudgingly waded through slurries of feminist rhetoric over the past decade, I’m led to conclude that the failings of feminists’ reasoning owe less to a shortage of intellect than to a willful failure of imagination. Ms. Newman is a novelist, from whom we might have expected better, and I’m more than cynical enough to wonder whether her chilling position wasn’t motivated to improve sales of her books among frothy feminist bluestockings.

A person possessed of an egalitarian imagination who was tasked with the same brief Ms. Newman assigned herself would be moved to satisfy questions like these: What happens to someone who has been accused of rape, and how does it feel?

Such exercise of imagination used to characterize what we call journalism—never mind creative writing.

Rape is broadly defined as any sort of intimate physical violation involving “private parts.” Is it likely that a goodly number of people who are accused of rape are forced to submit to invasive physical “examinations” that in a different context would be called assault? The question is rhetorical. Merely being taken into custody may make such examinations compulsory.

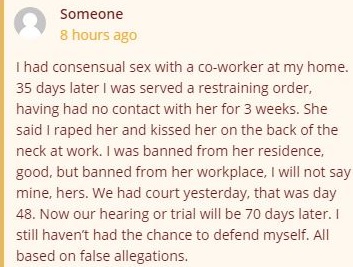

Ms. Newman’s thesis is that “it’s exceedingly rare for a false rape allegation to end in prison time” so being falsely accused of rape “almost never ha[s] serious consequences.”

By the same logic, since victims of rape are never imprisoned, being raped never has serious consequences.

The chinks in her reasoning are saliently obscene.

Ms. Newman also conveniently ignores that being accused of rape (among other felony crimes) may begin with incarceration, months of it. The accused’s being granted bail and being able to pay it is hardly a given—though it may be among members of Ms. Newman’s social caste.

Notably, Ms. Newman, a Brit, doesn’t bother to address the question of effects of false accusation to anyone who has actually felt them but instead limits her “investigation” to “academic studies, journalistic accounts, and cases recorded in the US National Registry of Exonerations.”

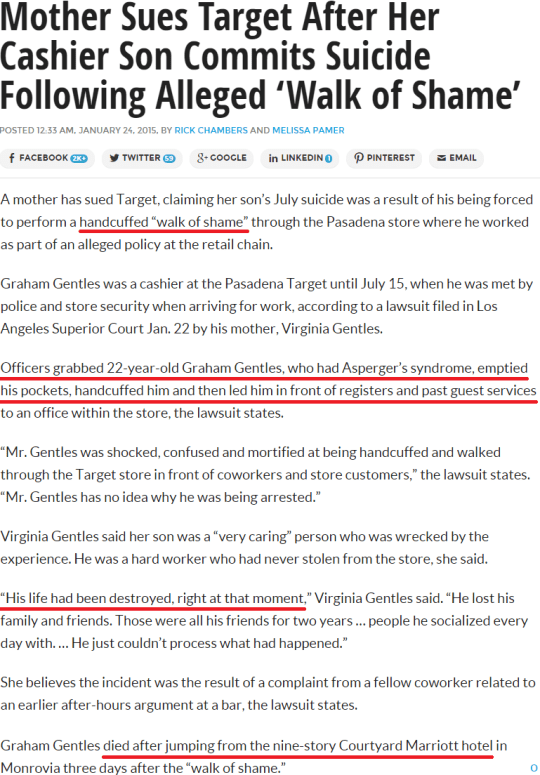

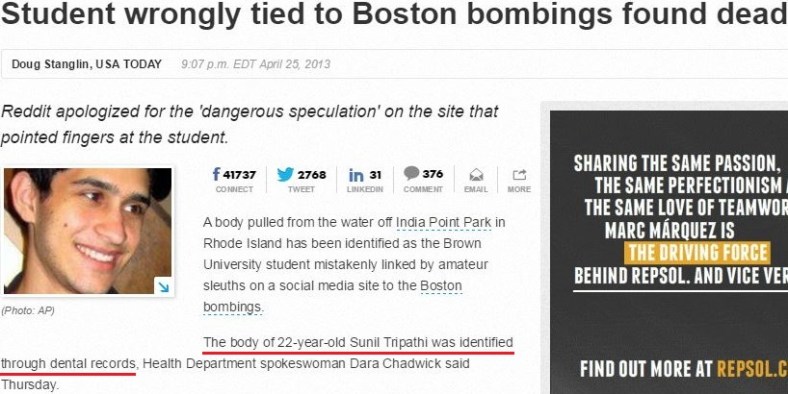

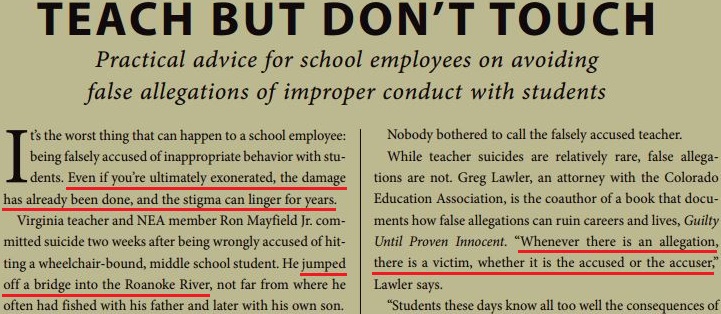

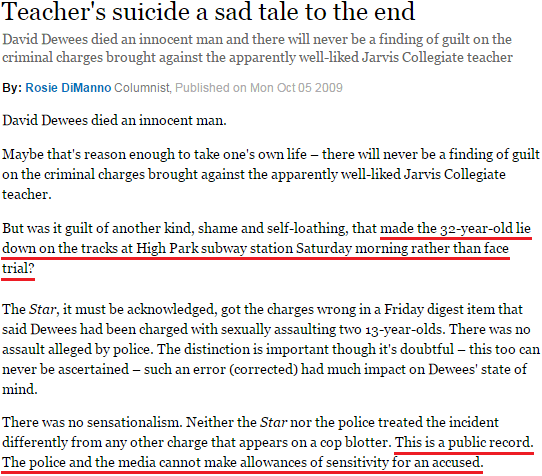

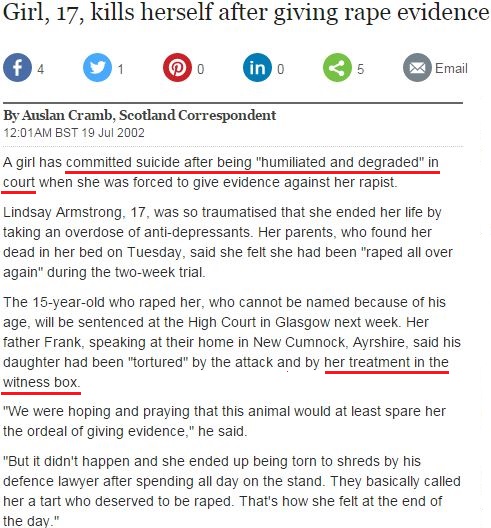

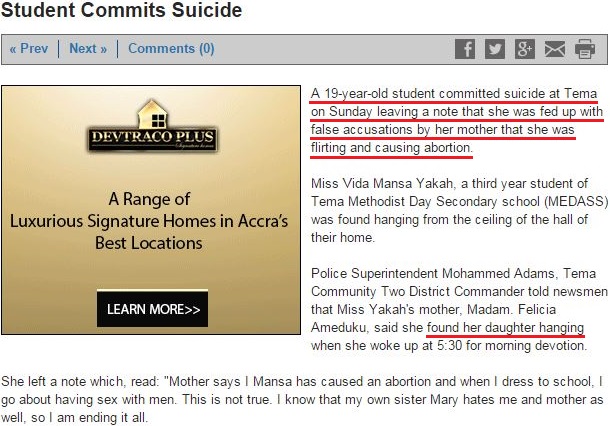

We’re to ignore, I guess, that she would hardly expect the effects of rape to be fully qualified by such sources. “Journalistic accounts” of false accusations of rape that this writer has digested have, besides, included such cases as these: a man falsely accused of rape, imprisoned, and then released only to learn his mother had committed suicide believing him to be a rapist; two women seducing a man and then accusing him of rape so their boyfriends didn’t learn what they’d got up to; women accusing men who spurned them or who disappointed expectations; a woman accusing a man of rape to have him murdered; men falsely accused of rape killing themselves. There is no dearth of “journalistic accounts” that contradict Ms. Newman’s assertion that being falsely accused is innocuous. See, for instance, Google.

Finally, Ms. Newman limits her contemplation to criminal cases. In this country, at least, home of the “National Registry of Exonerations,” rape accusations can also be brought in civil court, where they are adjudicated according to the very lowest standard of proof and can be credited by “default.” Faith in exonerations to provide a clear picture of the frequency of false accusation is faith in a golden calf. The conviction that only imprisonment is a “serious consequence” of being falsely accused, what’s more, is as execrable as the conviction that only rape victims who sustain permanent physical debility are worthy of sympathy.

Among a few others “types,” Ms. Newman fobs off instances of false accusation on the personality-disordered, whose prominent characterological trait is lack of empathy. Almost as defining is their resistance to self-criticism.

Copyright © 2017 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*This piece was originally titled: “Give Me Three Pieces of Information, and I Can Make Any Adult You Know a Rape Defendant for the Rest of His or Her Life: A Proposition Inspired by Feminist Writer Sandra Newman’s Claim that ‘False Rape Accusations Almost Never Have Serious Consequences.’” I decided, though, that articulating how I could do this might have motivated someone in earnest to apply the method—which is simple.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line.

Presuming to deny others’ pain, furthermore, because you believe you can quantify it or “imagine” what it “should” be like—that’s stepping way over the line. I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.

I do know what it is to be falsely accused, and the sources of pain are the same, only the suspicion and reproach aren’t an “expectation.” When you’re the target of damning fingers, suspicion and reproach inevitably ensue; they’re a given.