“I don’t know of any other provision in law in which people go to court and take out a civil action with the goal of handing over some of their power to a judge. When you get a restraining order, you relinquish your power to unilaterally consent to being contacted by the restrained party. As the ‘Notice to Restrained Person’ that the court gave me says, ‘If you violate this Order thinking that the Protected Person or anyone else has given you permission, you are wrong, and can be arrested and prosecuted. The terms of this Order cannot be changed by agreement of the parties. Only the court can change the order.’ The ‘Notice to Protected Person’ says ‘You cannot give the Restrained Person permission to change or ignore this Order in any way. Only the Court can change this Order.’”

—Blog respondent (July 2, 2015)

There’s an unexamined assumption that restraining orders “empower” those to whom they’re granted. Ask a feminist, and there’s a good chance this is exactly what she’ll say restraining orders do.

They don’t.

Restraining orders don’t empower anyone but police officers, judges, and prosecutors; they only take rights away. They prohibit normal, lawful conduct under penalty of punishment.

Those on the receiving end of an order are perceived to be the ones who are deprived of rights. But so, too, are those to whom orders are granted denied freedoms. Restraining order petitioners concede their power of choice, often unknowingly. Some petitioners of orders assume the value of an order is to give them the power of consent so they can choose or decline to associate with the defendant on the order according to their preference.

Petitioners have no discretionary rights. They forfeit their freedom of choice when they file allegations, and they do it voluntarily.

It isn’t “If I say yes, it’s yes; if I say no, it’s no.” It’s just no. A restraining order doesn’t bestow any entitlements; it erects a barrier.

An order of the court is an order, and that order can only be modified or revoked by the court. Observance of its prohibitions is never optional. Plaintiffs surrendered their say when they invited the state to play parent.

Returning to our imagined (straw) feminist, she might remark that restraining order plaintiffs don’t want anything to do with the people they petitioned orders against, so they haven’t been denied anything they cared about. But real life is seldom as black-and-white as a feminist’s imagination.

Some plaintiffs say they felt they were coerced into getting restraining orders and express resentment when they discover the consequences; others say they were ignorant of the import of orders. Some of the latter report that they renewed relations with the people they petitioned orders against and even moved in with them or had a child with them, assuming consent was theirs to give.

They desperately want to know what they can do when the people they petitioned orders against and then invited back into their lives are arrested and face jail time for contempt of court.

Similarly, domestic partners want to know how to communicate with the spouse or boy- or girlfriend they obtained an order against. They’re at a loss for how to deal with daily exigencies like home repairs and bills. They thought getting a court injunction was a measure to pacify conflict, not a complete severance of relations. They didn’t realize they were signing over their autonomy to the state.

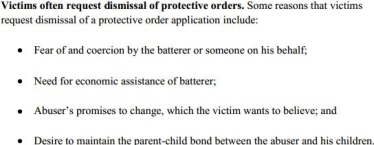

Predictably, a significant proportion of petitioners (reportedly as many as half) subsequently return to court to request that orders be withdrawn. A judge may agree, or s/he may not, according to his or her legislated prerogative. Some petitioners know to ask; some don’t know moving the court to dismiss an order is an option and instead act in violation of a judicial ruling that only exists because they requested it in the first place.

In “Protecting Victims from Themselves, but not Necessarily from Abusers: Issuing a No-Contact Order over the Objection of the Victim-Spouse” (2010), attorney Robert F. Friedman considers the constitutional right to autonomy that the advent of restraining orders has legislated away.

It gets worse.

Orders may also be issued by judges on their own initiative (sua sponte) if someone in a household reports a domestic altercation. They can even be issued if a third party (like a bystander or a neighbor) reports what s/he thinks is an altercation.

It’s not about who “presses charges.” That’s a misconception derived from TV. The state “presses charges.” The apparent “victim” has nothing to do with it. S/he can refuse to cooperate. S/he can even protest…and it doesn’t matter.

An order that’s imposed by the court, called a criminal or mandatory order, isn’t electively petitioned, so the person who’s named “the victim” can’t just go to a judge later on and ask that the order be canceled. Typically only the district prosecutor’s office can do this, and it has no compelling reason to.

Once the state is invited to be the arbiter of conflict, the rights of the parties involved become its to dictate. The only one “empowered” is Uncle Sam.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

Since I began culling various “

Since I began culling various “ If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary.

If the restraining order was petitioned in anger or the petitioner simply acted “without thinking,” withdrawing it is furthermore an ethical no-brainer, and it may be sufficient for the petitioner to tell the court that s/he no longer considers the order necessary. Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

Concerns about being prosecuted by the state for falsely alleging fear are unwarranted. Concerns about the state continuing to sniff around a plaintiff’s household, however, aren’t baseless. It happens.

fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing.

fulfilled in mere minutes, is agonizing.

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a

Learning the ins and outs of restraining order litigation has for this writer been an ongoing educational process bordering on a descent into hell that he’s only submitted to with a great deal of teeth-gnashing. In my state (Arizona), it’s possible for a plaintiff who’s petitioned for a restraining order in civil court to return to the same court and file a