“Could the number be between 3 and 8 percent? Absolutely. But it could be substantially higher than 8 percent; it could even be that 40 percent of rape accusations or more are false, though I’d bet against that. It’s possible that less than 3 percent of rape accusations are false, though again, I would offer good odds against that. The point is that we don’t know, and the groups that claim to know are wrong together.”

—Columnist Megan McArdle (June 4, 2015)

Megan McArdle is one of a handful of professional journalists (preeminent among them Cathy Young) who objectively negotiate the chasmal discrepancy between statistics that say false claims of rape are almost none and those that say they’re abundant.

In her Bloomberg View column “What We Don’t Know about False Claims of Rape,” Ms. McArdle surveys complications that foil attempts to arrive at a hard-and-fast figure. Issues like consent, culpability, what qualifies as rape and what doesn’t, and who gets to adjudicate and how—these muddy estimations that are already suspect, because purveyors and proponents of statistics are typically biased by one ideological or political perspective or another. They promote numbers that support their views; they opine.

This writer agrees with Ms. McArdle’s conclusions quoted above, and he finds especially agreeable her honest assessment of the ambiguities and her willingness to acknowledge them in the first place, because this willingness is rare.

False claims of rape made in civil court are not registered anywhere or by anyone.

I’m not a journalist; I’m an analyst. I don’t know what the truth is. I can criticize interpretations that betray flaws, but I don’t find anything in Ms. McArdle’s “findings” to fault. I do, though, detect a blind spot, and it’s a blind spot that’s universal.

What no one appears to know about false claims of rape is that they can be made in civil court. There are no incidence rates for how often this occurs…and there can’t be. Civil rulings, e.g., in restraining order cases, are based on a “preponderance of the evidence” and not on the certainty of individual accusations. The dismissal of a restraining order petition that alleges rape is not recorded anywhere as a “false rape claim”—it’s just rejected—and a verdict in favor of a plaintiff who alleges rape signifies only that a judge was convinced that the heft of his or her claims, possibly numerous, more likely than not indicated a sound basis for the award of a restraining order—and it may not signify that. Orders are also granted if defendants simply default by not appearing to contest the accusations.

False rape claims in civil court may never be accompanied by criminal investigations nor ever conclusively adjudicated. They’re invisible. They are, however, made, and though they may be completely unsubstantiated, they exert a material influence on judicial rulings that have binding legal consequences, consequences that can be extreme.

My wife moved out of my Virginia home in June 2014, and then about a week later announced that she’d had a miscarriage. In August 2014, I got a visit from police detectives wanting to question me about a rape report she’d filed against me, but I declined to speak with them, and was never charged. Beginning in November 2014, she obtained three temporary restraining orders against me, and finally got a permanent restraining order imposed against me in Colorado in January 2015, based on a claim of domestic abuse, stalking, sexual assault, and physical assault. Not wanting to invest money and emotional energy in fighting it, and knowing it would be hard for me to successfully contest it, I didn’t show up to the hearing.

The man quoted above obtained a divorce from his wife, who he alleges had a history of mental illness, in April 2015. Two months later, he learned she had given birth to a daughter in February, who was “presumptively” his. His ex-wife had apparently lied about having a miscarriage.

The information that he was a father reached the man when he was told his ex-wife had killed herself following her commitment for “suicidal depression, and because someone had reported that she had been hearing voices telling her to hurt or kill the child.”

The man was also told there was a “dependency and neglect petition pending” against him for his abandonment of a child he hadn’t known existed.

In the petition, the county attorney notes, “Respondent […] and Father have a history of domestic violence that includes, but may not be limited to, the issuance of temporary restraining orders in cases […], and the issuance of a permanent restraining order in case […], which was entered by default on January 16, 2015, placing the welfare of the child at risk.” The Colorado Children’s Code says that the court shall consider a parent’s “History of violent behavior” in determining whether he’s an unfit parent.

The purported “history of domestic violence” was not established in court and was based solely on his late ex-wife’s restraining order allegations, which started five months after she had moved out, which were made in minutes in another state, which the man denies, and which he never traveled cross-country to attempt to controvert. He hadn’t known his (then) wife was pregnant with his child when her serial accusations to the court began and despaired of his chances of successfully challenging them. He had ignorantly opted to “move on.”

Now his daughter is in the custody of her maternal grandparents, and the likelihood of her father’s ever realizing a role in her life is scant.

This man’s case is highlighted because it was brought to my attention only last week and is still fresh in my mind. Instances of false claims of rape accompanying restraining order petitions, however—including claims against women—have been reported repeatedly here, in comments and in search terms that draw visitors to the blog.

Not even a tentative estimate could be formulated on how often false rape claims are asserted in civil court, but this source of false claims should at least be recognized as inclusive among the unnavigable uncertainties.

Copyright © 2015 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*An alternative means of falsely alleging rape in civil court is exemplified here. An extreme case of a fraudulent rape claim’s being alleged on a restraining order petition is here.

To describe “your side” of nothing gives substance and dimensions to zero; it turns zero (a lie or lies) into something real—and this is what the civil court forces defendants to do…then it faults them for the stories it makes them tell about what was BS to begin with.

To describe “your side” of nothing gives substance and dimensions to zero; it turns zero (a lie or lies) into something real—and this is what the civil court forces defendants to do…then it faults them for the stories it makes them tell about what was BS to begin with.

Many of the posts published here in 2014 concern how we talk about violence against women.

Many of the posts published here in 2014 concern how we talk about violence against women. I had a brief but enlightening conversation years ago with a detective in my local county attorney’s office. I called to report

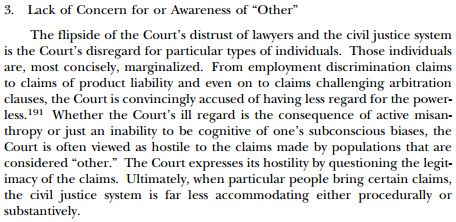

I had a brief but enlightening conversation years ago with a detective in my local county attorney’s office. I called to report  Those accused in civil court, though, are fish in a barrel. Judges are authorized to decide restraining order cases according to personal whim. There’s no “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” criterion to satisfy, and they know they have the green light to rule however they want.

Those accused in civil court, though, are fish in a barrel. Judges are authorized to decide restraining order cases according to personal whim. There’s no “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” criterion to satisfy, and they know they have the green light to rule however they want.