Battery, rape, child molestation—any heinous allegation imaginable can be made in a petition for a restraining order, and it can be made falsely without consequence to the accuser.

Victims of false allegations often ask incredulously, “Can somebody say that?”

There’s nothing that can’t be alleged to the courts (or, for that matter, to the police). There’s no such thing as “can’t allege.” A judge might view allegations of genocide or conspiracy with aliens to achieve global domination as suspect—or s/he might not. Certainly there’s nothing to stop a restraining order applicant from making these allegations, and there’s nothing to stop a judge from crediting them. Neither accusers nor judges are answerable to a literal burden of proof.

As the infamous David Letterman case shows, even the most outlandish allegations easily duck judicial radar. For anyone unfamiliar with the case, here’s Massachusetts attorney Gregory Hession’s synopsis and commentary (quoted from “Restraining Orders Out of Control”):

One day in December of 2005, Colleen Nestler came to Santa Fe County District Court in New Mexico with a bizarre seven-page typed statement and requested a domestic-abuse restraining order against late-night TV host David Letterman.

She stated, under oath, that Letterman seriously abused her by causing her bankruptcy, mental cruelty, and sleep deprivation since 1994. Nestler also alleged that he sent her secret signals “in code words” through his television program for many years and that he “responded to my thoughts of love” by expressing that he wanted to marry her.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Judge Daniel Sanchez issued a restraining order against Letterman based on those allegations. By doing so, it put Letterman on a national list of domestic abusers, gave him a criminal record, took away several of his constitutionally protected rights, and subjected him to criminal prosecution if he contacted Nestler directly or indirectly, or possessed a firearm.

Letterman had never met Colleen Nestler, and this all happened without his knowledge. Nonetheless, she requested that the order include an injunction requiring him not to “think of me, and release me from his mental harassment and hammering.” Asked to explain why he had issued a restraining order on the basis of such an unusual complaint, Judge Sanchez answered that Nestler had filled out the restraining-order request form correctly. After much national ridicule, the judge finally dismissed the order against Letterman. Those who don’t have a TV program and deep pockets are rarely so fortunate.

If allegations like these don’t trip any alarms, consider how much easier putting across plausible allegations is, plausible allegations that may be egregiously false and may include battery, rape, child molestation, or the commission of any other felony crimes.

What recent posts to this blog have endeavored to expose is that false allegations on restraining orders are very effective, because the “standard of evidence” applied to restraining order allegations both tolerates and rewards lying. The only thing that keeps false allegations reasonably in check is the fear that malicious litigants may have of their lies’ being detected. Normal people at least understand that lying is “bad” and that you don’t want to get caught doing it.

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and high-conflict litigants, who may have personality disorders and have no conscience, or whose thinking, like that of personality-disordered people’s, is overruled by intense emotions, self-identification as victims, and an urgent will to blame. Normal people may lie cunningly or viciously; high-conflict people may lie cunningly, viciously, compulsively, outrageously, and constantly.

To some degree at least, this understanding restricts all but the mentally ill, who may be delusional, and high-conflict litigants, who may have personality disorders and have no conscience, or whose thinking, like that of personality-disordered people’s, is overruled by intense emotions, self-identification as victims, and an urgent will to blame. Normal people may lie cunningly or viciously; high-conflict people may lie cunningly, viciously, compulsively, outrageously, and constantly.

The fear of getting caught in a lie is in fact baseless, because perjury (lying to the court) is prosecuted so rarely as to qualify as never. Most false litigants, however, don’t know that, so their lies are seldom as extravagant as they could be.

Often, though, their lies are extravagant enough to unhinge or trash the lives of those they’ve accused.

Appreciate that false allegations on restraining orders of battery, rape, child molestation, or their like don’t have to be proved. Restraining orders aren’t criminal prosecutions. Allegations just have to persuade a judge that the defendant is a sick puppy who should be kenneled. An allegation of battery, rape, or child molestation is just a contributing influence—except to the people who have to bear its stigma.

More typical than utterly heinous lies are devious misrepresentations. Accusations of stalking and untoward contact or conduct, which may simply be implied, are a common variety. The alleged use merely of cruel language may be very effective by itself. Consider how prejudicial a female plaintiff’s accusing someone (male or female) of forever calling her a “worthless bitch” could be. Substantiation isn’t necessary. Restraining order judges are already vigilantly poised to whiff danger and foul misconduct everywhere. In processes that are concluded in minutes, false or malicious accusers just have to toss judges a few red herrings.

Irrespective of the severity of allegations, the consequences to the fraudulently accused are the same: impediment to or loss of employment and employability, humiliation, distrust, gnawing outrage, depression, and despondency, along with possibly being menacingly barred access to home, children, property, and financial resource. This is all besides being forced to live under the ever-looming threat of further state interference, including arrest and incarceration, should additional false allegations be brought forth.

Even if no further allegations are made, restraining orders, which are public records accessible by anyone, are recorded in the databases of state and federal police…indefinitely.

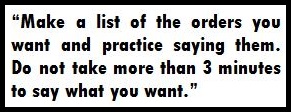

This “advice,” which urges restraining order applicants to rehearse, comes from the California court system and is offered on a page titled, “Ask for a Restraining Order.” The page’s title is not only invitational but can be read as an order itself: Do it. Note, also, that finalization of a restraining order may be based on less than “3 minutes” of testimony and that the court prefers it to be.

Recourses available to the falsely accused are few, and even lawsuits that allege abuse of process may face hurdles like claim preclusion (res judicata), which prohibits previously adjudicated facts from being reexamined. Never mind that the prior rulings may have been formulated in mere minutes based on fantasy and/or cooked allegations. Victims of defamation, fraud on the police and courts, and intentional infliction of emotional distress may moreover face stony indifference from judges, even if their lives have been entirely dismantled. And it should be stressed that attempting to rectify and purge their records of fraudulent allegations, which are established in minutes, can consume years of falsely accused defendants’ lives.

Recognizing that there are no bounds placed upon what false accusers may claim and that there are no consequences to false accusers for lying, the wonder is that more victims of lies aren’t alleged to be “batterers,” “rapists,” and “child molesters.”

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

No argument here.

No argument here. to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection.

to the procurement of restraining orders, which are presumed to be sought by those in need of protection. Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host

Such hearings are far more perfunctory than probative. Basically a judge is just looking for a few cue words to run with and may literally be satisfied by a plaintiff’s saying, “I’m afraid.” (Talk show host