Last month, I emphasized that the evils wrought by the restraining order process aren’t, strictly speaking, conspiratorial in origin. That’s basically true of the macrocosm. On the local level, though, they well may be.

It’s not uncommon for victims of restraining order abuse to report that their false accusers had confederates who spurred them on, lied for or sided with them, or put them up to making false allegations. Some report, alternatively, that they were coerced either by threat or urgent prompting by authorities. They were emotionally bullied into acting: Do it, Do it, Do it.

(Or: Do it or else. Women may be intimidated into seeking restraining orders against their husbands under threat from the state of eviction from government housing or having their children taken from them and fostered out.)

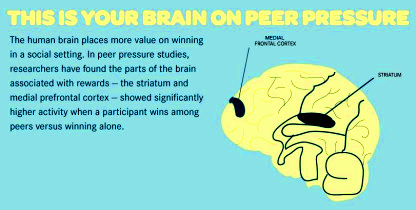

There’s something in us that thrills at seeing the ax fall on someone else’s neck. (If you haven’t read Shirley Jackson’s short story, “The Lottery,” do.) We get excited, like coyotes summoned to partake in the kill. We’re glad to be among the pack.

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

Although men regularly abuse the restraining order process, it’s more likely that tag-team offensives will be by women against men. Women may be goaded on by their parents or siblings, by authorities, by girlfriends, or by dogmatic women’s advocates. The expression of discontentment with a partner may be regarded as grounds enough for exploiting the system to gain a dominant position. These women may feel obligated to follow through to appease peer or social expectations. Or they may feel pumped up enough by peer or social support to follow through on a spiteful impulse. Girlfriends’ responding sympathetically, whether to claims of quarreling with a spouse or boy- or girlfriend or to claims that are clearly hysterical or even preposterous, is both a natural female inclination and one that may steel a false or frivolous complainant’s resolve.

And, sure, women will lie for women, too. This is something I’ve witnessed personally. Academic types, in particular—women who’ve been cultivated in the feminist hothouse—may well nurse a great deal of animosity toward men in general and be happy for any opportunity to indulge it (manipulating the court can make a Minnie Mouse feel like Arnold Schwarzenegger). A contrasting but also correspondent dynamic is mothers-in-law’s lying about their daughters-in-law (or their sons’ girlfriends). It’s not for nothing that we have a word like catty.

I’ve never heard of men urging other men to acquire restraining orders. When men are egged on, it’s reportedly by a woman who’s jealous of a rival and wants to see her suffer, but men are just as likely to exploit false allegations successfully put over on the courts to smear their victims. My impression is that this is less about attention-seeking than rubbing salt in the wound and fortifying the credibility of their frauds—though attention, particularly female, may be a welcome dividend.

An exceptional case is the person with an attention-seeking personality disorder, whose concoctions may be so extravagantly persuasive that s/he has everyone s/he knows siding with him or her. S/he creates his or her own sensation. Perfectly innocent and well-intentioned chumps may testify on such a person’s behalf firmly convinced that they’re acting nobly (which reinforces their own resolve to self-defensively stick to their stories, even if they’re later given cause to doubt them). Domineering personality types like pathological narcissists, who come in both genders and compulsively lie with sociopathic cold-bloodedness, may even coerce or seduce others into assuming their perspectives. They generate peer pressure and alliance. Narcissists are walking Jiffy Pops in search of a little heat to rub against.

Everything to do with restraining orders is about pressure. Possibly the same could be said about all court procedures involving conflict (real or hyped), but this is particularly true of the restraining order process. Those who game the system often do so to gain attention and approbation or to appease others’ expectations.

If invoking this state procedure failed or ceased to excite drama, its applicant pool would dry up faster than a Visine tear.

Copyright © 2014 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge).

The phrase restraining order fraud, too, needs to gain more popular currency, and I encourage anyone who’s been victimized by false allegations to employ it. Fraud in its most general sense is willful misrepresentation intended to mislead for the purpose of realizing some source of gratification. As fraud is generally understood in law, that gratification is monetary. It may, however, derive from any number of alternative sources, including attention and revenge, two common motives for restraining order abuse. The goal of fraud on the courts is success (toward gaining, for example, attention or revenge). Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).

Consider: If someone falsely circulates that you’re a sexual harasser, stalker, and/or violent threat—possibly endangering your employment, to say nothing of savaging you psychologically—you can report that person to the police, seek a restraining order against that person for harassment, and/or sue that person for defamation and intentional infliction of emotional distress. If, however, that person first obtains a restraining order against you based on the same false allegations—which is simply a matter of filling out a form and lying to a judge for five or 10 minutes—s/he can then circulate those allegations, which have been officially recognized as legitimate on an order of the court, with impunity. Your credibility, both among colleagues, perhaps, as well as with authorities and the courts, is instantly shot. You may, besides, be subject to police interference based on further false allegations, or even jailed (arrest for violation of a restraining order doesn’t require that the arresting officer actually witness or have incontrovertible proof of anything). And if you are arrested, your credibility is so hopelessly compromised that a false accuser can successfully continue a campaign of harassment indefinitely. Not only that, s/he can expect to do so with the solicitous support and approval of all those who recognize him or her as a “victim” (which may be practically everyone).