“Let’s face it, sometimes you get wrongfully accused of harassing someone. Perhaps it is a vendetta, a figment of the accuser’s imagination, or something else. […] The mere accusation, even if unfounded, can be devastating to your reputation and may imperil your chances of employment, could lead to the loss of your right to possess a firearm, [restrict] where and when you can go places, etc. (Note: These matters become public records that can be easily searched and identified.) For example, we often find that neighbors who become ‘unneighborly’ will seek an order restricting how close you can come to their home, and whether you are to stay away from certain ‘areas,’ etc. Additionally, if left unchallenged, then often the mere allegation that you violated the injunction against harassment may land you in custody.”

—Attorney Joseph A. Velez

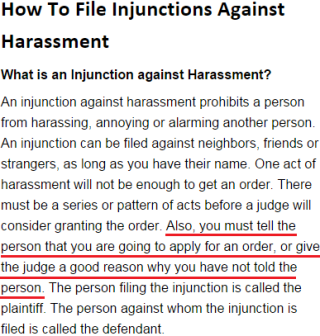

The “Injunction Against Harassment” is one of three types of restraining (or “protective”) order issued in Arizona. The title of the instrument is deceptive. Allegations by petitioners aren’t limited to harassment and may be of anything, including violent threat or assault, or even sexual violation.

An “Order of Protection” is what a complainant files against someone who shares a residence with him or her; an “Injunction Against Harassment” is what a complainant files if his or her relationship with the defendant is other than domestic (e.g., against a friend, neighbor, or stranger). Conduct alleged on either order may be identical.

It may also be false. Orders aren’t hard to obtain, including on the basis of exaggerations or outright fraud.

Here are some facts of which the recipient of an Arizona Injunction Against Harassment should be aware:

-

Highlighted in this explanation from the Tucson City Court, which applies everywhere in the state of Arizona, is a statutory requirement that the judge who issued you an Injunction Against Harassment may have carelessly overlooked.

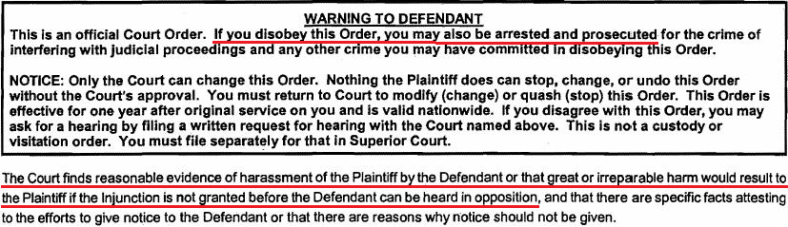

The injunction may be appealed, and an appeals hearing may be requested at any time during the order’s term of effect (one year). It need not be requested immediately. A.R.S § 12-1809(H). You must apply to be granted a hearing, and you must apply in writing. (Instructions appear at the top of the document’s first page.)

- Postponing the appellate procedure allows you more time to gather evidence and witness testimony, and save money to procure the services of a lawyer. Being issued an order of the court can be intimidating and bewildering, and a defendant’s impulse may be to drop everything and respond immediately. There’s much, however, to recommend deferment.

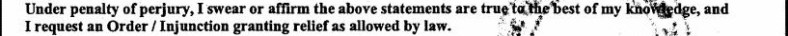

- Satisfaction of A.R.S § 12-1809(E) requires that the petitioner of the order must have presented to the judge “specific facts attesting to [his or her] efforts to give notice to the defendant or reasons supporting the plaintiff’s claim that notice should not be given.” This means if the petitioner of the order did not notify you prior to applying for an ex parte order from the court, and no good reasons were provided to the judge why you weren’t notified, then judicial approval of the order was against the law.

- Judicial derelictions are grounds for an order’s dismissal.

Restraining order defense may be a specialization of some criminal attorneys, and the defendant seeking legal counsel would do well to search for a specialist in his or her city online and/or call around.

Copyright © 2018 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

*The author of this post successfully had an injunction against harassment dismissed last summer.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.

Appreciate that the court’s basis for issuing the document capped with the “Warning” pictured above is nothing more than some allegations from the order’s plaintiff, allegations scrawled on a form and typically made orally to a judge in four or five minutes.