Restraining orders were designed to be easily obtained so that at-risk women could quickly and conveniently gain relief from dicey situations.

Conceptually, the motive behind their legislative enactment is pretty hard to fault.

Common sense, however, should warn us (and should have warned lawmakers from the start) that a government process that’s quick and convenient is one that’s going to be abused.

And when there’s money to be made from that process, moreover—in this case by everyone from attorneys, police departments, and courts to social workers, feminist advocacy groups, and psychotherapists—it’s one to be doubly dubious of.

Over the three decades since restraining orders were instituted, both their breadth of applicability and punitive force have steadily magnified.

If the standards that determine when a restraining order is warranted have changed at all, however, those standards have only slackened.

Practice has outstripped principle.

Restraining orders may now be issued to arrest any minor conflict—including, for example, Facebook annoyances—but still retain their original implications: violence, predatory stalking, and other extreme misconduct.

Even the paper applications remain the same. Restraining orders are one-size-fits-all documents.

And their residue never just evaporates. Restraining order recipients may be denied employment even years later, because the issuance of these instruments remains a matter of public record. They may even be recorded in registries for convenient public access. Some job applications, what is more, explicitly ask if a potential employee has “been the subject of a restraining order.” Doctrinaire advocates of restraining orders still perpetuate the illusion that they’re only issued to domestic abusers and other social malefactors, so the public presumption is that if you’ve received a restraining order, you’re a batterer, stalker, or some other form of sexual or criminal deviant—and clearly not a great candidate for employment anywhere. Nor a great candidate, for that matter, to adopt a child or share someone else’s life.

The law applies a double-standard. On the one hand, it regards restraining orders as civil misdemeanors and no big deal. Recipients of restraining orders are supposed to mind them for their duration and then shrug them off: c’est la vie. On the other hand, it won’t hesitate to judge a person for his or her having received a restraining order, and may regard and treat a restraining order recipient like a criminal.

As one respondent to this blog points out, the safeguards against criminalizing someone unjustly have been entirely circumvented:

Before these restraining order injunctions came about, it was up to the police and the district attorney to move forth prosecution. The police investigate crimes, and the district attorney helps prosecute crimes. If something did not appear to be severe, deserving punishment, and a problem to society or its individuals, it was brushed off.

In comes restraining orders.

Yes, restraining orders can help an individual develop criminal allegations against another individual in civil court. However, a judge generally has the power to rule over simple things, such as harassment, whereby a bench trial can occur. Many other things, such as assault, are criminal allegations, whereby a person is granted a right to a jury.

It is the right to a jury that has become degenerated throughout these proceedings. As such, members of society have been allowed to attack one another without any observation of a “reasonable person” standard. The judge, no longer impartial, becomes the reasonable person.

Restraining order legislation all but automates the process of saddling a person indefinitely with criminal imputations that are legitimated by a judge based solely on a brief interview with the restraining order applicant alone and that need never be proven at all, let alone to a jury of the restraining order recipient’s peers.

Restraining orders have made determining who’s a criminal and who isn’t a completely bureaucratic process. What should demand extreme deliberation has become an arbitrary call.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

The 148 search engine terms that appear below—at least one to two dozen of which concern false allegations—are ones that brought readers to this blog between the hours of 12 a.m. and 7:21 p.m. yesterday (and don’t include an additional 49 “unknown search terms”).

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

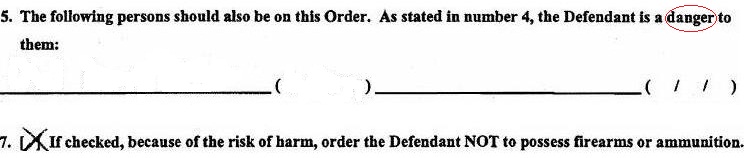

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

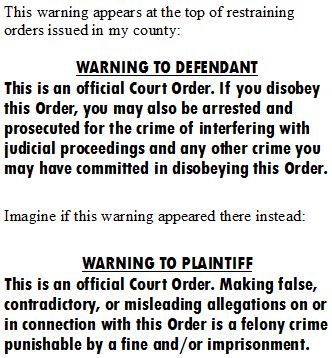

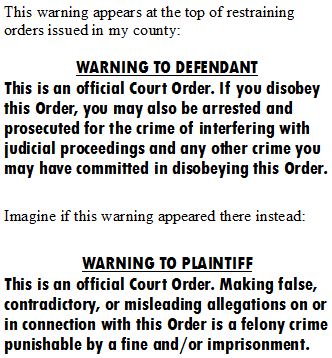

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.