Whoever came up with restraining orders must have been a marvel at Twister.

Though they’re billed as civil instruments, restraining orders threaten their recipients with criminal consequences and may be based on allegations of a criminal nature, for example, stalking, sexual harassment, the threat of violence, or assault.

The standard of substantiation applied to criminal allegations is “proof beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

Since restraining orders are “civil” instruments, however, their issuance doesn’t require proof beyond a reasonable doubt of anything at all. Approval of restraining orders is based instead on a “preponderance of evidence.” Because restraining orders are issued ex parte, the only evidence the court vets is that provided by the applicant. This evidence may be scant or none, and the applicant may be a sociopath. The “vetting process” his or her evidence is subjected to by a judge, moreover, may very literally comprise all of five minutes.

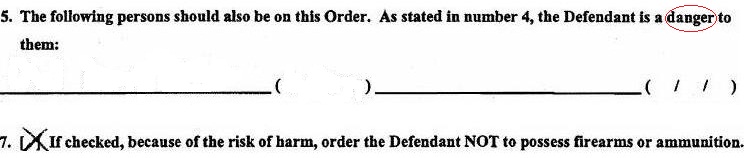

Based on allegations leveled in this hiccup of time by a person with an obvious interest in seeing you suffer, you are now officially recognized as a stalker, batterer, and/or violent crank and will be served at your home with a restraining order (and possibly evicted from that home) by an agent of the nanny state: “Sign here, please” (“and don’t let the door hit you on your way out”).

The application of a standard of proof to restraining order allegations is circumvented entirely: what a plaintiff claims you are becomes the truth of you. The loophole is neatly conceived (and it’s exploited thousands of times a day). Your record may be corrupted by criminal allegations like those enumerated above based on crocodile tears and arrant lies spilled on a boilerplate bureaucratic form. And these allegations may tear your life apart.

Abuse of restraining orders for malicious ends is a court-catered cakewalk.

How easily it’s exploited for foul purposes, in fact, is the restraining order process’s claim to distinction from other judicial procedures. Even by veteran officers of the court, false allegations made in restraining order petitions are routinely accepted at face value. The reasons for this are manifold:

- Judges are trained to regard women’s plaints as legitimate and may never question this prejudice, because it’s shared by the society at large. And to appear to be fair, a judge may apply the same prejudice to allegations brought by men against women.

- No judge wants to be the one who refused a restraining order to someone who later comes to harm, because (a) he will have failed a constituent in need and be perceived as having had a hand in her (or his) injury; and (b) because he will be publicly vilified, likely fired or forced to resign, and possibly sued.

- Innocent defendants never succeed in making a stink that would put a judge’s career in jeopardy: erring on the side of a plaintiff poses no threat to a judge’s job security, while erring on the side of a defendant may cost him not only his job but considerably more.

- It’s in the financial interests of local jurisdictions and their judges to appear to be “cracking down” on society’s bad eggs.

Lying to obtain a restraining order, therefore, is a cinch. Any lowlife can do it.

Disinterest (a.k.a. objectivity, fairness, impartiality, yadda-yadda-yadda) is the essential canon of judicial ethics. Since it’s one that clearly doesn’t obtain in the restraining order process, this judicial procedure is also distinguished from others by its inherent corruptness.

This corruptness is obscured from public awareness by yet another knot. Innocent defendants, in endeavoring to extricate themselves from false allegations—for example, as this author has by clamoring in a blog—cannot help but appear to be the fixated “deviants” that those false allegations represent them to be. The more they resist the allegations, the more they seem to corroborate them.

Appearances are not only the predominant grounds for restraining orders; appearances are what motivated their sketchy conception in the first place (“We’ve got to show we care”), and appearances are what preserve the corrupt process from which they issue from being recognized for the disgrace that it is.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

You know, a box like you’ll find on any number of bureaucratic forms. Only this box didn’t identify her as white or single or female; it identified her as a batterer. A judge—who’d never met her—reviewed this form and signed off on it (tac), and she was served with it by a constable (toe) and informed she’d be jailed if she so much as came within waving distance of the plaintiff or sent him an email. The resulting distress cost her and her daughter a season of their lives—and to gain relief from it, several thousands of dollars in legal fees.

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

The ethical, if facile, answer to his or her (most likely her) question is have the order vacated and apologize to the defendant and offer to make amends. The conundrum is that this would-be remedial conclusion may prompt the defendant to seek payback in the form of legal action against the plaintiff for unjust humiliation and suffering. (Plaintiffs with a conscience may even balk from recanting false testimony out of fear of repercussions from the court. They may not feel entitled to do the right thing, because the restraining order process, by its nature, makes communication illegal.)

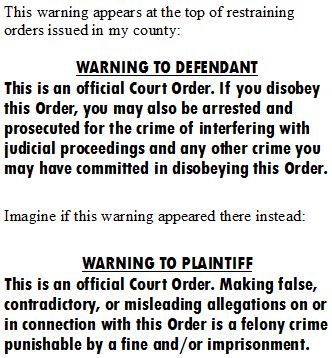

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

If the courts really sought to discourage frauds and liars, the consequences of committing perjury (a felony crime whose statute threatens a punishment of two years in prison—in my state, anyhow) would be detailed in bold print at the top of page 1. What’s there instead? A warning to defendants that they’ll be subject to arrest if the terms of the injunction that’s been sprung on them are violated.

As any attorney will tell you (and would have told you 10, 15, or even 20 years ago), it’s a cakewalk for a woman to find a judge who’ll rubberstamp an application for a restraining order. (If one judge refuses to grant her request, she can always shop around until she finds another who will.) These instruments are dispensed like kleenex. Herein lies the obscenity. When this process is abused—which may be routinely—it can derail lives.

As any attorney will tell you (and would have told you 10, 15, or even 20 years ago), it’s a cakewalk for a woman to find a judge who’ll rubberstamp an application for a restraining order. (If one judge refuses to grant her request, she can always shop around until she finds another who will.) These instruments are dispensed like kleenex. Herein lies the obscenity. When this process is abused—which may be routinely—it can derail lives.