Fair is a word that appears prominently in ethical canons drafted to define the methodologies and behaviors expected of judges (which canons are consolidated into states’ codes of judicial conduct, compendia of rules and principles that in the administration of restraining orders are more often paid lip service than scrupulous attention). An obligation of using the word fair is tolerating having done to you what you do to others.

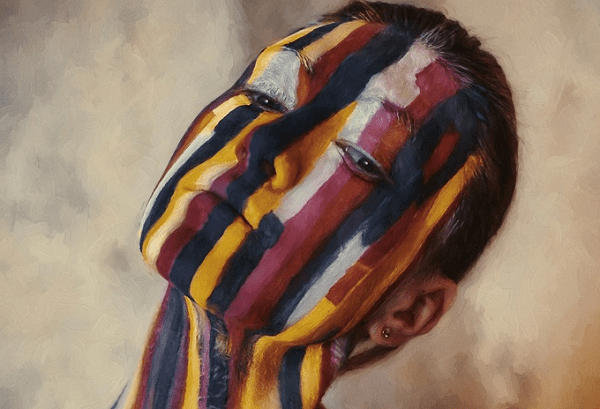

Among the unfair aspects of how restraining orders are administered is the judicial application of a generic standard to defendants (that is, recipients of restraining orders). Positive matches are facilely constructed (sight unseen) between any John or Jane Doe who’s had a finger pointed at him or her—very possibly by a malicious accuser—and some paradigmatic caricature bad guy, the “Grim Creeper,” the original template for whose debauched and demonic dimensions was the much-hyped domestic batterer of 30 years ago.

Anyone targeted by this process, based on real allegations as innocuous as texting too much or on completely false allegations, is treated like the Grim Creeper.

By this standard, the scorn and ignominy earned by some judges should be borne by all of them, that is, if judicial logic is that because some restraining order defendants are bad eggs, all restraining order defendants should be regarded as bad eggs and publicly vilified, it only follows that if some judges are rotten egg omelets, all judges should be suspect. Fair is fair.

This is all a very circumspect introduction to my sharing that in randomly Googling “crazy judge,” I stumbled upon a page on “5 Shockingly Crazy Judges Who Presided Over Modern Courts.” It answered my query with the following case studies:

- A Michigan judge, who reportedly handled sexual misconduct cases and was married, is distinguished for having texted a shirtless photo of himself to one of his female bailiffs and later responding to the alleged impropriety, “Yep, that’s me. No shame in my game.” He went on to sleep with a defendant who appeared before him to settle a child support dispute (and, she says, knock her up), allegedly repaying her sexual favors with preferential treatment.

- An Oklahoma judge attained infamy by repeatedly exposing himself in his courtroom over a period of years and using a penis pump on a number of occasions during jury trials. Semen stains were turned up not only on his robes but on the carpet and the chair behind his bench.

- A Florida judge responded to a threatening comment made by a defendant by producing a .38-caliber revolver and declaring, “There’s one bullet in the cylinder. Do you want to take your best shot? If you’re going to take a shot, you had better score, because I don’t miss.” He then rested the gun on his bench for the remainder of the proceeding.

- A Georgia judge pulled a firearm during a trial and prompted a witness, the alleged victim of a sexual assault whose attacker had held a gun to her head, to shoot her attorney.

- An Illinois judge whose tenure on the bench had already spanned 18 years, 18 years marked by allegations of mental illness, was reelected in 2012 despite being found “legally insane” by a psychiatrist. She was in court the next day on charges of shoving a court deputy (following her being ejected from her courtroom for engaging in a 45-minute rant and followed by her throwing a set of keys at a security checkpoint). Her annual salary: $182,000.

And the list goes on.

Consider that all restraining order defendants may feel treated like sex offenders, violent menaces, and nuts irrespective of what they have or haven’t done, and consider it in light of these judges’ actual conduct.

Two of these judges were suspended (only one without pay), one was transferred, and one resigned. Only one of these judges was sentenced to prison. And none were issued restraining orders, which make millions of people vulnerable to incarceration every year based merely on finger-pointing.

Aside from this quibble, do these cases really signify anything but that no occupation is immune from attracting the odd screwball?

Yes, in fact they do. Significant is that in more than one of these cases, the behaviors that eventually drew censure were allowed to continue for a period of many years (and were obviously known to members of their staff). This fact highlights the laxity of judicial oversight. A more significant implication of these cases is that only extreme judicial misconduct really gets zeroed in on. Practitioners of rhetoric (essay writers, for example) will use extreme or even wildly fictional scenarios (hyperbole) to emphasize implications, because we perceive best what’s writ large and luridly, and seeing the big implications allows us to grasp the smaller ones. If judges are capable of engaging in and getting away with the extreme misbehaviors exemplified in the cases enumerated above, possibly for years, it follows that less sensational infractions and lapses occur all the time and are winked at. This is not only significant but significant to hundreds or thousands of peoples’ lives every day.

Get it?

Having now concluded this excursion, let us return, shall we, to that never-never land we’re supposed to occupy where defendants have black mustachios they twist between their fingers, and judges, properly tasked with corralling the bad guys, have gleaming teeth, flaxen motives, and minds as white and wide as the Lone Ranger’s Stetson.

Copyright © 2013 RestrainingOrderAbuse.com

The reason I’m revisiting Dr. Dutton’s book in this post is that several of the jobs it identifies as most likely to draw psychopaths are ones in the legal profession and government.

The reason I’m revisiting Dr. Dutton’s book in this post is that several of the jobs it identifies as most likely to draw psychopaths are ones in the legal profession and government.

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled

That’s why I’m particularly impressed when I encounter writers whose literary protests are not only controlled but very lucid and balanced. One such writer maintains a blog titled  Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

Casual charlatanism, though, is hardly an accomplishment for people without consciences to answer to. And rubes and tools are ten cents a dozen.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

A principle of law that everyone ensnarled in any sort of legal shenanigan should be aware of is stare decisis. This Latin phrase means “to abide by, or adhere to, decided things” (Black’s Law Dictionary). Law proceeds and “evolves” in accordance with stare decisis.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides.

This means defendants can be denied access to the family pet(s), besides. I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused.

I had an exceptional encounter with an exceptional woman this week who was raped as a child (by a child) and later violently raped as a young adult, and whose assailants were never held accountable for their actions. It’s her firm conviction—and one supported by her own experiences and those of women she’s counseled—that allegations of rape and violence in criminal court can too easily be dismissed when, for example, a woman has voluntarily entered a man’s living quarters and an expectation of consent to intercourse has been aroused. Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male.

Lapses by the courts have piqued the outrage of victims of both genders against the opposite gender, because most victims of rape are female, and most victims of false allegations are male. As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

As many people who’ve responded to this blog have been, this woman was used and abused then publicly condemned and humiliated to compound the torment. She’s shelled out thousands in legal fees, lost a job, is in therapy to try to maintain her sanity, and is due back in court next week. And she has three kids who depend on her.

The

The  Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called

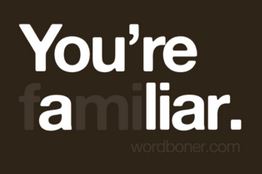

Not many years ago, philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a treatise that I was amused to discover called  The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better.

The logical extension of there being no consequences for lying is there being no consequences for lying back. Bigger and better. The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts?

The sad and disgusting fact is that success in the courts, particularly in the drive-thru arena of restraining order prosecution, is largely about impressions. Ask yourself who’s likelier to make the more impressive showing: the liar who’s free to let his or her imagination run wickedly rampant or the honest person who’s constrained by ethics to be faithful to the facts? Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states.

Judicial misbehavior is often complained of by defendants who’ve been abused by the restraining order process. Cited instances include gross dereliction, judge-attorney cronyism, gender bias, open contempt, and warrantless verbal cruelty. Avenues for seeking the censure of a judge who has engaged in negligent or vicious misconduct vary from state to state. In my own state of Arizona, complaints may be filed with the Commission on Judicial Conduct. Similar boards, panels, and tribunals exist in most other states.

Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied

Restraining orders occupy an exceptional status among complaints made to our courts, because their defendants (recipients) are denied

Those most dramatically impacted by restraining order abuse, its victims, are typically only heard to peep and grumble here and there.

Those most dramatically impacted by restraining order abuse, its victims, are typically only heard to peep and grumble here and there.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.

Following Tylenol’s being tampered with in 1981, everything from diced onions to multivitamins requires a safety seal. Naive trust was violated, and legislators responded.

Dr. Charles Corry, president of the

Dr. Charles Corry, president of the

So how is it so many men are railroaded through a process that may be initiated on no evidence at all, may strip them of their most valued investments and every bit of social and financial equity they’ve built in their lives—kids, home, money, property, business, and reputation—and may ensure that they’re never able to recover what they’ve been deprived of?

So how is it so many men are railroaded through a process that may be initiated on no evidence at all, may strip them of their most valued investments and every bit of social and financial equity they’ve built in their lives—kids, home, money, property, business, and reputation—and may ensure that they’re never able to recover what they’ve been deprived of?

It shouldn’t be any mystery why with millions of restraining orders being issued each year in the Internet age complaints of abuses aren’t louder and more numerous: stigma.

It shouldn’t be any mystery why with millions of restraining orders being issued each year in the Internet age complaints of abuses aren’t louder and more numerous: stigma.

This question pops up a lot.

This question pops up a lot.